- POWER

- MORALITY

- SOCIETY

The article examines the socio-political views of Thomas More. Particular attention is paid to the presentation of his concept of the state.

- Improving the information policy of the Russian Federation

- Basic rules for working with the media of local governments

- Integrated land policy as an object of political science research

Thomas More is an English philosopher and writer who adheres to humanistic views. His main book is "Utopia", in which he depicts his ideal society in the form of a fantastic island-state. He follows many thinkers of the Renaissance, who saw limitations in the cult of individualism, which became the ideological core of the Renaissance, and turned to understanding sociality, without which a full-fledged existence is impossible and which needs to be improved. He considers the method of building such a society to be convincing people of the need for such a future. He considers universal morality to be the main tool for the life of society.

More saw the Reformation as a threat to the church and society, criticized the religious views of Martin Luther and William Tyndale and, while serving as Lord Chancellor, prevented the spread of Protestantism in England. Refused to acknowledge Henry VIII head of the Church of England and considered his divorce from Catherine of Aragon invalid. In 1535 he was executed under the Act of Treason. In 1935 he was canonized as a saint of the Catholic Church. Most likely, his views should be characterized as traditionalism, but the revolutionary spirit of his book speaks of his inherent sympathy for innovation, for moderate liberalism.

The main topic More's thoughts became problems of the socio-political structure. He did not create an original socio-philosophical concept based on a deeply developed theoretical philosophy, however, his substantive approach to considering social problems, which nevertheless traces his attitude to the problem of the relationship between the individual and society. Religious beliefs occupy an important place in More's worldview. On the one hand, he is a model Catholic, opposing Protestantism and the Church of England. On the other hand, he is a humanist who understands the need scientific thinking, enlightenment of the people of his era. We believe that he is a follower of the Catholic philosopher Thomas Aquinas, who proposed to seek a union between religion, science and education. The same position is defended by a number of Muslim theologians.

The main problem socio-political structure T. More considered the issue of property, which gives rise to many social ills - inequality, oppression, envy, etc. He saw a cure for social ills in replacing private property with public property. T. More knew well the social and moral life of contemporary England. His sympathy for the plight of the masses was reflected precisely in the book “Utopia”, which is permeated with the influence of Plato’s ideas, and above all his work “The State”.

The most specific feature of T. More’s socio-philosophical concept is its anti-individualistic interpretation public life, imagined by him in his version ideal state. Consistent anti-individualism requires the abolition of private property, equalizing everyone in consumption (we subsequently discover this idea in the theory of scientific communism of Marxism). And if Plato private property is absent only in the ruling classes, then in the utopian state of T. More it is absent in everyone. T. More tried to reduce the state to big family, in which there can be no stratification of property, because within the family, private property loses its meaning. At the same time, it is necessary for people to recognize this loss and accept it.

Following the example of Plato, T. More considers justice and adherence to laws to be the main pillars of the state. Moreover, the inhabitants of Utopia are subject not so much to legal as to ethical laws: they have very few written laws. It is interesting that such a view on the regulation of social life was expressed by the classics of Marxism-Leninism. The inhabitants of Utopia have their own religion, more ancient than Christianity. Its content boils down to the belief in the existence of a single divine being(Parent) spilled all over the world. Here we see a contradiction in the views of the Catholic More and the ideologist of Utopia. However, such contradictions are also revealed on a number of other issues of this utopian socialist.

The methodology for analyzing society proposed by More is hardly justified. But for its time it was progressive, it showed that there were other ways of social structure. Unfortunately, More saw no other way to explain social development, multidimensionality of historical and sociological knowledge.

Based on the above, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- Since T. More argues that the imperfection of the individual existence of people in the state is determined by the established system of property, this actually means an objective approach to the relationship between the individual and society, in which the social whole in the form of social relations influences individuals, turning them into suffering objects.

- By changing the social whole, one can achieve a change in individual existence for the better.

Bibliography

- Davletgaryaeva R.G. Education as a determining factor further development humanity // Modern world: economics, history, education, culture collection scientific works. Ufa, 2005. pp. 301-304.

- Davletgaryaeva R.G. Universal ethics and the crisis of modern civilization // Features of development agro-industrial complex on modern stage materials of the All-Russian scientific-practical conference within XXI International specialized exhibition. 2011. pp. 182-183.

- Rakhmatullin R.Yu., Semenova E.R. Traditionalism and liberalism in the light of the philosophy of law // Scientific Bulletin Omsk Academy Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia. 2014. No. 1 (52). pp. 41-44.

- Rakhmatullin R.Yu., Semenova E.R. Traditionalism and liberalism in legal and pedagogical space // Professional education V modern world. 2014. No. 1 (12). pp. 19-26.

- Semenova E.R. Ideas of traditionalism and liberalism in the philosophy of law // Almanac of modern science and education. 2013. No. 3 (70). pp. 161-163.

- Rakhmatullin R., Semenova E. Thomism of the unity of the religious and scientific knowledge // Science i studio. 2015. T. 10. pp. 288-291.

- Ziatdinova F.N., Davletgaryaeva R.G. Basic principles of organization and management in the education system // Bulletin of the Bashkir State Agrarian University. 2013. No. 2 (26). pp. 130-132.

- Rakhmatullin R.Yu. Religion and science: the problem of relationship (using the example of Islam) // Young scientist. 2014. No. 4. P. 793-795.

- Rakhmatullin R.Yu. The problem of objectivity historical knowledge or how a single history textbook is possible // European Social Science Journal. 2014. No. 8-3 (47). pp. 69-73.

Thomas More was born into the family of a famous London lawyer, a royal judge. After two years of study at Oxford University, Thomas More, at the insistence of his father, graduated from law school and became a lawyer. Over time, More gained fame and was elected to the English Parliament.

IN early XVI century, Thomas More became close to the circle of humanists John Colet, in which he met Erasmus of Rotterdam. Subsequently, More and Erasmus had a close friendship.

Under the influence of his humanist friends, the worldview of Thomas More himself was formed - he began to study the works of ancient thinkers, having learned Greek, he began translating ancient literature.

Without leaving literary works, Thomas More continues his political activities - he was the sheriff of London, chairman of the House of Commons of the English parliament, and received a knighthood. In 1529 More took the highest government post in England - became Lord Chancellor.

But in the early 30s of the 16th century, More's position changed dramatically. The English king Henry VIII decided to carry out church reform in the country and become the head of the church. Thomas More refused to swear allegiance to the king as the new head of the church, resigned as Lord Chancellor, but was accused of treason and in 1532 imprisoned in the Tower. Three years later, Thomas More was executed.

Thomas More entered the history of philosophical thought primarily as the author of a book that became a kind of triumph of humanistic thought. More wrote it in 1515–1516. and already in 1516, with the active assistance of Erasmus of Rotterdam, the first edition was published entitled “A very useful, as well as entertaining, truly golden book about the best structure of the state and about the new island of Utopia.” Already during his lifetime, this work, briefly called “Utopia,” brought More worldwide fame. The word “Utopia” itself was coined by Thomas More, who composed it from two Greek words: “ou” “not” and “topos” - “place”. Literally, “Utopia” means “a place that does not exist” and it is not for nothing that More himself translated the word “Utopia” as “Nowhere”.

More's book tells about a certain island called Utopia, whose inhabitants lead perfect image life and established an ideal political system. The name of the island itself emphasizes that we're talking about about phenomena that do not exist and, most likely, cannot exist in real world.

The book is written in the form of conversations between the traveler-philosopher Raphael Hythloday, Thomas More himself and the Dutch humanist Peter Aegidius. The narrative consists of two parts. In the first part, Raphael Hythloday expresses his critical opinion about what he saw current situation in England. In the second, written, by the way, earlier than the first, Raphael Hythloday outlines the Utopian way of life to his interlocutors.

It has long been noticed, and the author himself does not hide this, that “Utopia” was conceived and written as a kind of continuation of Plato’s “Republic” - like Plato, Thomas More’s work gives a description of an ideal society, as humanists imagined it XVI century. Therefore, it is quite understandable that in “Utopia” one can find a certain synthesis of the religious-philosophical and socio-political views of Plato, the Stoics, the Epicureans with the teachings of the humanists themselves and, above all, with the “philosophy of Christ”.

Just like Plato, More sees the main principle of life in an ideal society in one thing - society should be built on the principle of justice, which is unattainable in the real world. Raphael Hythloday denounced his contemporaries: “Unless you consider it fair when all the best goes to the most bad people, or you will consider it successful when everything is distributed among very few, and even they do not live prosperously, while the rest are completely unhappy.”

The Utopians managed to create a state built on the principles of justice. And it is not for nothing that Hythloday describes with admiration “the wisest and holiest institutions of the Utopians, who very successfully govern the state with the help of very few laws; and virtue is valued there, and with equality there is enough for everyone.”

How is it possible for a just society to exist? Thomas More turns to the ideas of Plato and through the mouth of his hero declares: “There is only one way for social well-being - to declare equality in everything.” Equality is assumed in all spheres - economic, social, political, spiritual, etc. But first of all, in the property sphere, private property is abolished in Utopia.

It is the absence of private property, according to Thomas More, that creates the conditions for the birth of a society of universal justice: “Here, where everything belongs to everyone, no one doubts that no one individual will not need anything, if only he makes sure that the public granaries are full." Moreover, "because there is no stingy distribution of goods here, there is not a single poor person, not a single beggar." And - "although those who have nothing there, are all, however, rich."

In the same row stands Thomas More’s thesis about the dangers of money - money in Utopia is also abolished and, therefore, everything has disappeared negative points, generated by money: thirst for profit, stinginess, desire for luxury, etc.

However, the elimination of private property and money is not an end in itself for Thomas More - it is just a means to ensure that social conditions of life provide an opportunity for development human personality. Moreover, the very fact of the voluntary consent of the Utopians to live without private property and money is associated primarily with high moral qualities inhabitants of the island.

Raphael Hythloday describes the Utopians in full accordance with those ideals harmoniously developed personality who inspired the thinkers of the Renaissance. All Utopians are highly educated, cultured people who know how and love to work, combining physical labor with mental labor. Being most seriously concerned with the ideas of the public good, they do not forget to engage in their own physical and spiritual development.

In Utopia, according to Thomas More, complete religious tolerance reigns. On the island itself, several religions coexist peacefully, while no one has the right to argue on religious issues, because this is regarded as a state crime. The peaceful coexistence of different religious communities is due to the fact that faith in the One God, which the Utopians call Mithra, is gradually spreading on the island.

In this sense, More was undoubtedly influenced by the teaching of Marsilio Ficino about “universal religion.” But at the same time, Thomas More goes further than Ficino, for he directly connects the idea of the One God with the pantheistic idea of the Divine nature: “Despite the fact that in Utopia not everyone has the same religion, all its types, despite their diversity and multitude , in unequal paths, as it were, flock to a single goal - to the veneration of the Divine nature." And pantheism is expressed by More with greatest strength of all previous humanists.

The religious beliefs of the Utopians are harmoniously combined with their excellent knowledge of secular sciences, primarily philosophy: “...They never talk about happiness, so as not to combine with it some principles taken about religion, as well as philosophy, using the arguments of reason, without this, they believe that the study of true happiness itself will be weak and powerless." And in a surprising way philosophical teachings Utopians are exactly similar to the teachings of humanists, although, as you know, the island of Utopia is in no way connected with another land.

The religious and philosophical views of the Utopians, combined with the principles of equality, create conditions for high level development of moral principles on the island. Talking about the virtues of the inhabitants of Utopia, Thomas More, through the mouth of Raphael Hythloday, again sets out a humanistic “apology for pleasure.” Indeed, in the understanding of humanists, human virtues themselves were directly related to spiritual and bodily pleasures.

In essence, Utopia is a humanistic image of a perfect community. This image harmoniously combines the triumph of the individual with public interests, because society itself was created in order to enable human talents to flourish. At the same time, everyone understands perfectly well that utopia means that their well-being and spiritual freedom are directly related to that social order universal justice, which is set on Utopia.

The very image of a utopian community, where private property, monetary circulation, privileges, luxury production, etc. were abolished, became a kind of culmination of humanistic dreams of an “ideal state.”

More's early life

Thomas More (More, Latin Morus) - wonderful English political figure and humanist. Born in 1478 or 1480 in London. More's father was a member of the Court of King's Bench; an Old Testament man, he raised his children in strict discipline. Archbishop Morton of Canterbury, a friend of the new enlightenment, noticed the boy's abilities and sent him to Oxford University. Here or soon after, More became close to Erasmus, who influenced him strong influence; Erasmus dedicated his famous satire to More, as the wittiest person of its time. The Oxford circle, which More joined, associated ideas with classicism religious reform, trying to merge with the teachings of Plato early Christianity, mainly in the teachings of the ap. Pavel. At one time, More indulged in asceticism, wore a hair shirt, and thought about entering a monastery; subsequently his piety became more relaxed, internal character. The study of the Greek language, considered at that time a dangerous innovation, aroused the fear of Father More; the young humanist had to become a lawyer. He did not, however, abandon his previous studies and gave lectures on Augustine’s “De civitate Dei” to a large gathering of the best young people. In 1504 More appeared as a deputy in the parliament summoned by Henry VII after an interval of seven years; here More came out with opposition to the king's monetary demands and caused his disfavor, as a result of which he had to retire to privacy. The accession of Henry VIII (1509), who was still friends with More and other humanists as a prince, opened up broad hopes for the latter. More was attracted to the court: in 1514 he became a member of the Privy Council and was elevated to the nobility.

"Utopia" by More

At this time (1516), More's most famous work, Utopia, was published, where the social, pedagogical, and religious ideals of the Renaissance are revealed in the form of a political novel. "Utopia" splits into two parts. The first contains a sharp satire on the England of Henry VII, pointing out the contradiction between the development of poverty and crime - on the one hand, the ruinous, warlike policies of the government and the useless cruelty of the court - on the other; The main task of the reform is outlined here - the reorganization social order and education. In the second part, More depicts happy life citizens of the fantastic island of "Utopia" in the distant west. In Utopia, while preserving the monogamous family and patriarchal relations, communism was implemented in relation to land, tools and products of labor. More's "Utopia" differs from Plato's state in that work is obligatory for everyone and is considered an honor. Slavery is permitted, but represents an exceptional phenomenon: slave prisoners of war or slave criminals are provided with heavy and unpleasant work. Normal work is farming. Citizen-workers, divided, according to More, into “surnames,” move in groups alternately from city to village and back; labor was reduced to a six-hour standard. Morals are distinguished by extreme simplicity and moderation. Education and spiritual pleasures are available to everyone. Women are culturally placed on an equal footing with men. Scientists occupy large public positions. “Utopia” allows religious tolerance for a wide variety of beliefs, provided that their representatives do not have a spirit of persecution or inclination to rebellion. The priests, few in number, are chosen by secret ballot; this is an exclusive calling for heroic and sublime natures, surrounded by extraordinary honor. With general contentment, the inhabitants of More's Utopia avoid war if possible or wage it through foreign mercenaries; but the law of war remains cruel.

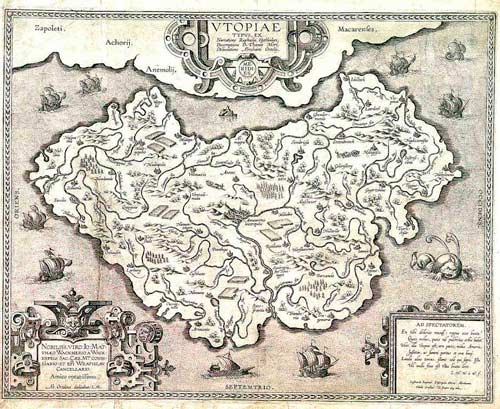

Map of the imaginary island of Utopia, artist A. Ortelius, c. 1595

More's chancellorship

More, apparently, began to become disillusioned with the king early on. He and his friends were upset that Henry VIII was carried away by war, instead of devoting himself to the cause of enlightenment. Nevertheless, More continued to rise in the favor of the king: he was, at the request of the king, elected speaker of the House of Commons, fulfilled important diplomatic missions. Beginning in 1525, the king sought More's company, often sent for him and often visited More at his home in Chelsea, constantly starting conversations with him about science and theology. More, not trusting the king, reluctantly succumbed to these caresses and avoided the court whenever possible. In 1523, More, who had until then enjoyed the favor of the all-powerful Cardinal Wolsey, aroused his anger when, as speaker, he became the head of parliament, which rejected the ruler’s monetary demands. But the king protected More from Wolsey’s persecution, and after his fall, in 1529, he made More chancellor (this was the first time that this position was filled by someone other than a prelate or a representative of the highest aristocracy). More gained extraordinary popularity in this position by the incorruptible and conscientious court which he established. Negative attitude The king's divorce from his first wife forced him in 1532 to abandon the chancellorship and service in general, as a result of which he found himself in extremely cramped material conditions.

More's execution

In 1534, More was asked to recognize the illegality of the king's first marriage and the legality of the inheritance rights of children from his second wife. More agreed to the second, since Parliament could change the order of succession, but refused the first. For this refusal he was sent to prison. At first the imprisonment was not severe; but More's position worsened when he refused to recognize the royal supremacy. This led to him being accused of treason. On July 6, 1535, More was beheaded. More was one of the most ardent heralds of the new enlightenment in England. In his writings (cf. especially epist. ad Dorpium) he insisted on studying Greek language and printing the Greek text of the Bible. But More, like Erasmus, only with greater conviction, remained until the end of his days on the basis of the Catholic Church. He was repulsed by the dogmatism and intolerance of Protestants; he did not want to see them as representatives of reform. Commitment to old church ultimately put him in conflict with the principles of religious tolerance carried out in Utopia. As chancellor, More encountered strong sectarianism in England; preachers of reform under him were punished as rebels: they were sent to prison, and More did not prevent the bishops from sentencing them to death. Of the foreigners who visited More, the artist Holbein became especially close to him, leaving beautiful portraits of More and a description of his home life. Catholic Church subsequently tried to present More as a martyr for the faith; Pope Leo XIII in 1886 included More among the blessed.

Editions of the works of Thomas More in the 16th century

More's works were published: English - in 1530, in London, Latin - in 1563, in Basel. In addition to those mentioned, a collection of Latin languages stands out among them. epigrams and biographies of York kings of the 15th century. "Utopia" was first published in 1516 in Louvain, under the title "Libellus aureus nec minus salutans quam festivus de optimo reipublicae statu de que nova insula Utopia."

Books about Thomas More

Of More's contemporaries, his biographies were written by his son-in-law Roper (published in English 1551, in Danish 1558, reprinted many times) and Stapleton (1588)

Roodhart "Thomas More". Nuremberg, 1829

Baumstark. "Thomas More". Freib., 1879

Walter "Thomas More and His Age". Tour, 1868

Bridgett. "Thomas More". London, 1883

Books about More's Utopia

Kautsky "Thomas More and His Utopia". Stuttgart, 1888

Kimwechter. "A Novel about the State". Vienna, 1891

Whipper R. "More's Utopia" (magazine "World of God", March 1896)

Thomas More's biography of the English lawyer, philosopher, and humanist writer is outlined in this article. Thomas More's core ideas outline his vision of life in society.

Thomas More short biography

English writer and statesman born on February 7, 1478 in London in the family of a lawyer. He received his first education at St. Anthony's Grammar School. At the age of 13 he served in the archbishop's house as a page. During 1490-1494 he studied at Oxford, studying legal sciences, classical languages. At the university he met Erasmus of Rotterdam. Thomas accepted monastic tonsure and until the end of his life he led a restrained lifestyle, prayed and observed fasts.

In 1502, More worked as a lawyer and taught law, and in 1504 he was elected to parliament. By advocating a reduction in fees for King Henry VII, Thomas fell into disgrace and withdrew from political activity. He was able to return to national activities in 1509, when the king died.

In 1510 he was again elected to parliament, convened by Henry VIII. Thomas was appointed to the post of undersheriff of the capital and assistant judge.

In 1515 he began work on his first book. Utopia, which was born in 1516, was appreciated by the monarch.

In 1518, Thomas More joined the circle of members of the royal privy council. In 1521 he was elected to the Star Chamber and received a knighthood with huge plots of land. In the period from 1525-1527, the writer served as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and from 1529 - the post of Lord Chancellor.

Name: Thomas More

Age: 57 years old

Activity: lawyer, philosopher, humanist writer

Family status: was married

Thomas More: biography

Thomas More is a famous humanist writer, philosopher and lawyer from England, who also served as Lord Chancellor of the country. Thomas More is best known for his work called Utopia. In this book, using a fictional island as an example, he outlined his vision of an ideal socio-political system.

The philosopher was also active public figure: the era of the Reformation was alien to him, and he created obstacles to the spread of the Protestant faith to English lands. Refusing to recognize Henry VIII's status as head of the English Church, he was executed under the Act of Treason. In the 20th century, Thomas More was canonized as a Catholic saint.

Childhood and youth

The biography of Thomas More begins in the family of the London judge of the High Court of Justice, Sir John More. Thomas was born on February 7, 1478. His father was known for integrity, honesty and high moral principles, which largely determined his son’s worldview. The son of the famous judge received his first education at St. Anthony's Grammar School.

At the age of thirteen, More the Younger received the position of page under Cardinal John Morton, who for some time served as Lord Chancellor of England. Morton liked the cheerful, witty and inquisitive young man. The cardinal said that Thomas would certainly “become a marvelous man.”

At sixteen, More entered Oxford University. His teachers were the greatest British lawyers of the late 15th century: William Grosin and Thomas Linacre. Study was given young man relatively easily, although already at that time he began to be attracted not so much by the dry formulations of laws as by the works of the humanists of that time. So, for example, Thomas independently translated into English language biography and work “The Twelve Swords” by the humanist from Italy Pico della Mirandola.

Two years after entering Oxford, More Jr., at the direction of his father, returned to London in order to improve his knowledge of English law. Thomas was a capable student and, with the help of experienced lawyers of the time, learned all the pitfalls of English law and became a brilliant lawyer. At the same time, he was interested in philosophy, studied the works of ancient classics (especially Lucian and), improved Latin and Greek and continued to write own compositions, some of which were started while still studying at Oxford.

Thomas More’s “guide” to the world of humanists was Erasmus of Rotterdam, whom the lawyer met at a gala reception with the Lord Mayor. Thanks to his friendship with Rotterdamsky, the aspiring philosopher entered the circle of humanists of his time, as well as the circle of Erasmus. While visiting the house of Thomas More, Rotterdamsky created the satire “In Praise of Folly.”

Presumably, the young lawyer spent the period from 1500 to 1504 in the London Carthusian monastery. However, he did not want to completely devote his life to serving God and remained in the world. However, from then on, Thomas More did not abandon the habits acquired during his life in the monastery: he got up early, prayed a lot, did not forget a single fast, practiced self-flagellation and wore a hair shirt. This was combined with a desire to serve and help the country.

Policy

In the early 1500s, Thomas More taught law while practicing law, and in 1504 he became a Member of Parliament for the merchants of London. While working in Parliament, he more than once allowed himself to openly speak out against the tax arbitrariness that King Henry VII inflicted on the people of England. Because of this, the lawyer fell out of favor in the highest echelons of power and was forced to abandon his political career for some time, returning exclusively to legal work.

Simultaneously with the conduct of judicial affairs, at this time Thomas increasingly confidently tried his hand at literature. When in 1510 the new ruler of England, Henry VIII, convened a new Parliament, the writer and lawyer again found a place in the highest legislature countries. At the same time, More received the position of assistant sheriff of London, and five years later (in 1515) he became a member of the English embassy delegation sent to Flanders for negotiations.

Then Thomas began working on his “Utopia”:

- The author wrote the first book of this work in Flanders and completed it soon after returning home.

- The second book, the main content of which is a story about a fictitious island in the ocean, which was supposedly recently discovered by researchers, More mainly wrote earlier, and upon completion of the first part of the work he only slightly corrected and systematized the material.

- The third book was published in 1518 and included, in addition to previously written material, the author’s “Epigrams” - an extensive collection of his poetic works, made in the genre of poems, verses and epigrams themselves.

“Utopia” was intended for enlightened monarchs and humanistic scientists. She had a great influence on the development of the utopian ideology and mentioned the abolition of private property, equality of consumption, socialized production, etc. Simultaneously with the writing of this work, Thomas More was working on another book - “History Richard III».

The country of Utopia, described by Thomas More

The country of Utopia, described by Thomas More King Henry VIII highly appreciated the gifted lawyer's Utopia and in 1517 decided to appoint him as his personal advisor. So the famous utopian joined the Royal Council, received the status of royal secretary and the opportunity to work on diplomatic assignments. In 1521, he began to sit in the highest English judicial institution - the Star Chamber.

At the same time he received a knighthood, land grants and became assistant treasurer. Despite the successful political career, he remained a modest and honest man, whose desire for justice was known throughout England. In 1529, King Henry VIII granted the loyal adviser the highest government post - the position of Lord Chancellor. Thomas More became the first person from the bourgeoisie who managed to occupy this post.

Works

The greatest value among the works of Thomas More is the work “Utopia”, which includes two books.

The first part of the work is a literary and political pamphlet (a work of an artistic and journalistic nature). In it, the author expresses his views on how imperfect social and politic system. More criticizes death penalty, ironically ridicules the debauchery and parasitism of the clergy, firmly opposes the fencing of communal people, and expresses disagreement with the “bloody” laws on workers. In the same part, Thomas also proposes a program of reforms designed to correct the situation.

The second part presents More's humanistic teachings. The main ideas of this doctrine boil down to the following: the head of state should be a “wise monarch”, private property and exploitation should be replaced by socialized production, labor is obligatory for everyone and should not be exhausting, money can only be used for trade with other countries (monopoly on which belongs to the state leadership), the distribution of products should be carried out according to needs. More's philosophy assumed complete democracy and equality, despite the presence of a king.

"Utopia" became the basis for subsequent development utopian teachings. In particular, she played a significant role in the development of the humanistic position of such a famous philosopher as Tommaso Campanella. To others significant work Thomas More's History of Richard III, the credibility of which is still debated: some researchers believe the book historical work, others – rather artistic. The utopian also wrote many translations and poetic works.

Personal life

Even before the Renaissance was enriched with the famous work of Thomas More and before he began to occupy high positions in the state, the humanist married seventeen-year-old Jane Colt from Essex. This happened in 1505. She was a quiet and kind girl and soon bore her husband four children: a son, John, and daughters, Cecile, Elizabeth and Margaret.

In 1511, Jane died due to fever. Thomas More, not wanting to leave his children without a mother, soon married a wealthy widow, Alice Middleton, with whom he lived happily until his death. She also had a child from her first marriage.

Death

For Thomas More, quotations from his works were not just fiction– he deeply believed in all the provisions of his teaching and remained a religious person. Therefore, when Henry VIII wanted to divorce his wife, More insisted that only the Pope could do this. The role of the latter at that time was played by Clement VII, and he was against divorce proceedings.

As a result, Henry VIII severed ties with Rome and set out to create the Anglican Church in home country. Soon the king's new wife was crowned. All this caused such indignation in Thomas More that he not only resigned as Lord Chancellor, but also helped the nun Elizabeth Barton publicly condemn the king's behavior.

Soon Parliament passed the “Act of Succession to the Throne”: all english knights had to take an oath recognizing the children of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn as legitimate and refusing to recognize any authority over England except that of the representatives of the Tudor dynasty. Thomas More refused to take the oath and was imprisoned in the Tower. In 1535 he was executed for high treason.

In 1935 he was canonized as a Catholic saint.