1 . The labor movement, which was then just taking its first steps, cannot yet be taken into account here

3. The tsarism used troops against students, as well as against peasants, and temporarily closed St. Petersburg and Kazan universities. The Peter and Paul Fortress was then overflowing with arrested students. Someone’s brave hand inscribed “St. Petersburg University” on the wall of the fortress.

4. Chernyshevsky was arrested by gendarme colonel Fyodor Rakeev - the same one who in 1837 took the body of A.S. for secret burial in the Svyatogorsk Monastery. Pushkin and thus took part in Russian literature twice.

5. It is amazing that almost all Soviet historians, led by Academician. M.V. Nechkina, although they were indignant at Kostomarov’s perjury, considered Chernyshevsky the author of the proclamation “To the Master’s Peasants” (in order to sharpen his revolutionary spirit). Meanwhile, “not a single argument usually given in favor of Chernyshevsky’s authorship stands up to criticism” ( Demchenko A.A. N.G. Chernyshevsky. Scientific biography. Saratov, 1992. Part 3 (1859-1864) P. 276).

6. For details, see: Chernyshevsky case: Sat. docs / Comp. I.V. Powder. Saratov, 1968.

7. Certificate of A.I. Yakovlev (a student of Klyuchevsky) from the words of the historian himself. Quote By: Nechkina M.V. IN. Klyuchevsky. The story of life and creativity. M., 1974. P. 127.

8. It was the Ishuta people who attempted to carry out the first of eight known attempts to liberate Chernyshevsky from Siberia.

9 . Before his execution, Muravyov himself interrogated him and threatened: “I will bury you alive in the ground!” But on August 31, 1866, Muravyov died suddenly, and he was buried a day earlier than Karakozov.

10. Its text was published several times. See for example: Shilov A.A. Catechism of a revolutionary // Struggle of classes. 1924. No. 1-2. Until recently, M.A. was considered the author of the Catechism. Bakunin, but, as is clear from the correspondence of Bakunin with Nechaev, first published in 1966 by the French historian M. Confino, Nechaev composed the “Catechism”, and Bakunin was even shocked by it so much that he called Nechaev an “abrek”, and his “Catechism” - “catechism of abreks.”

"Going to the People"

From the beginning of the 70s, the populists took up the practical implementation of Herzen’s slogan “To the people!”, which had previously been perceived only theoretically, with an eye to the future. By /251/ that time, the populist doctrine of Herzen and Chernyshevsky was supplemented (mainly on issues of tactics) by the ideas of the leaders of the Russian political emigration M.A. Bakunina, P.L. Lavrova, P.N. Tkachev.

The most authoritative of them at that time was Mikhail Aleksandrovich Bakunin, a hereditary nobleman, friend of V.G. Belinsky and A.I. Herzen, a passionate opponent of K. Marx and F. Engels, a political emigrant since 1840, one of the leaders of the uprisings in Prague (1848), Dresden (1849) and Lyon (1870), sentenced in absentia by the tsarist court to hard labor, and then twice (by the courts Austria and Saxony) - to death. He outlined the program of action for Russian revolutionaries in the so-called Appendix “A” to his book “Statehood and Anarchy.”

Bakunin believed that the people in Russia were already ready for revolution, because need had brought them to such a desperate state when there was no other way out but rebellion. Bakunin perceived the spontaneous protest of the peasants as their conscious readiness for revolution. On this basis, he convinced the populists to go to the people(i.e. into the peasantry, which was then actually identified with the people) and call them to revolt. Bakunin was convinced that in Russia “it costs nothing to raise any village” and you just need to “agitate” the peasants in all villages at once for all of Russia to rise.

So, Bakunin's direction was rebellious. Its second feature: it was anarchist. Bakunin himself was considered the leader of world anarchism. He and his followers opposed any state in general, seeing in it the primary source of social ills. In the view of the Bakuninists, the state is a stick that beats the people, and for the people it makes no difference whether this stick is called feudal, bourgeois or socialist. Therefore, they advocated a transition to stateless socialism.

From Bakunin's anarchism flowed specifically– populist apolitism. The Bakuninists considered the task of fighting for political freedoms unnecessary, but not because they did not understand their value, but because they sought to act, as it seemed to them, more radically and more advantageously for the people: to carry out not a political, but a social revolution, one of the fruits of which would be itself, “like smoke from a furnace,” and political freedom. In other words, the Bakuninists did not deny the political revolution, but dissolved it in the social revolution.

Another ideologist of populism in the 70s, Pyotr Lavrovich Lavrov, emerged in the international political arena later than Bakunin, but soon gained no less authority. An artillery colonel, philosopher and mathematician of such brilliant talent that the famous academician M.V. Ostrogradsky admired him: “He is even quicker than me.” Lavrov was an active revolutionary, /252/ a member of “Land and Freedom” and the First International, a participant in the Paris Commune of 1870, a friend of Marx and Engels. He outlined his program in the magazine “Forward!” (No. 1), which published from 1873 to 1877 in Zurich and London.

Lavrov, unlike Bakunin, believed that the Russian people were not ready for revolution and, therefore, the populists should awaken their revolutionary consciousness. Lavrov also called on them to go to the people, but not immediately, but after theoretical preparation, and not for rebellion, but for propaganda. As a propaganda trend, Lavrism seemed to many populists more rational than Bakunism, although others were repelled by its speculativeness, its focus on preparing not the revolution itself, but its preparers. “Prepare and only prepare” - this was the thesis of the Lavrists. Anarchism and apolitism were also characteristic of Lavrov's supporters, but less so than the Bakuninists.

The ideologist of the third direction was Pyotr Nikitich Tkachev, a candidate of rights, a radical publicist who fled abroad in 1873 after five arrests and exile. However, Tkachev’s direction is called Russian Blanquism, since the famous Auguste Blanqui previously advocated the same positions in France. Unlike the Bakuninists and Lavrists, the Russian Blanquists were not anarchists. They considered it necessary to fight for political freedoms, seize state power and certainly use it to eradicate the old and establish a new system. But since. the modern Russian state, in their opinion, did not have strong roots either in economic or social soil (Tkachev said that it “hangs in the air”), the Blanquists hoped to overthrow it by force parties conspirators, without bothering to propagandize or revolt the people. In this respect, Tkachev as an ideologist was inferior to Bakunin and Lavrov, who, despite all the disagreements between them, agreed on the main thing: “Not only for the people, but also through the people.”

By the beginning of the mass “going to the people” (spring 1874), the tactical guidelines of Bakunin and Lavrov had spread widely among the populists. The main thing is that the process of accumulating strength has been completed. By 1874, the entire European part of Russia was covered with a dense network of populist circles (at least 200), which managed to agree on the places and timing of the “circulation”.

All these circles were created in 1869-1873. under the impression of Nechaevism. Having rejected Nechaev's Machiavellianism, they went to the opposite extreme and rejected the very idea of a centralized organization, which was so ugly refracted in /253/ Nechaevism. The circle members of the 70s did not recognize either centralism, discipline, or any charters or statutes. This organizational anarchism prevented the revolutionaries from ensuring coordination, secrecy and efficiency of their actions, as well as the selection of reliable people into circles. Almost all the circles of the early 70s looked like this - both Bakuninist (Dolgushintsev, S.F. Kovalik, F.N. Lermontov, “Kiev Commune”, etc.), and Lavrist (L.S. Ginzburg, V.S. Ivanovsky , “Saint-Zhebunists”, i.e. the Zhebunev brothers, etc.).

Only one of the populist organizations of that time (albeit the largest) retained, even in the conditions of organizational anarchism and exaggerated circleism, the reliability of the three “Cs”, equally necessary: composition, structure, connections. It was the Great Propaganda Society (the so-called “Chaikovites”). The central, St. Petersburg group of the society arose in the summer of 1871 and became the initiator of the federal association of similar groups in Moscow, Kyiv, Odessa, and Kherson. The main composition of the society exceeded 100 people. Among them were the largest revolutionaries of the era, then still young, but soon gaining world fame: P.A. Kropotkin, M.A. Nathanson, S.M. Kravchinsky, A.I. Zhelyabov, S.L. Perovskaya, N.A. Morozov and others. The society had a network of agents and employees in different parts of the European part of Russia (Kazan, Orel, Samara, Vyatka, Kharkov, Minsk, Vilno, etc.), and dozens of circles were adjacent to it, created under his leadership or influence. The Tchaikovites established business connections with the Russian political emigration, including Bakunin, Lavrov, Tkachev and the short-lived (in 1870-1872) Russian section of the 1st International. Thus, in its structure and scale, the Great Propaganda Society was the beginning of an all-Russian revolutionary organization, the forerunner of the second society “Land and Freedom”.

In the spirit of that time, the “Chaikovites” did not have a charter, but an unshakable, albeit unwritten, law reigned among them: the subordination of the individual to the organization, the minority to the majority. At the same time, the society was staffed and built on principles directly opposite to Nechaev’s: they accepted into it only comprehensively tested (in terms of business, mental and necessarily moral qualities) people who interacted with respect and trust towards each other - According to the testimony of the “Chaikovites” themselves, in their organization “They were all brothers, everyone knew each other like members of the same family, if not more.” It was these /254/ principles of relationships that from now on laid the basis for all populist organizations up to and including “Narodnaya Volya”.

The society's program was developed thoroughly. It was drafted by Kropotkin. While almost all the populists were divided into Bakuninists and Lavrists, the “Chaikovites” independently developed tactics, free from the extremes of Bakunism and Lavrism, designed not for a hasty revolt of the peasants and not for “training the preparers” of the rebellion, but for an organized popular uprising (of the peasantry under worker support). To this end, they went through three stages in their activities: “book work” (i.e. training of future organizers of the uprising), “worker work” (training mediators between the intelligentsia and the peasantry) and directly “going to the people”, which the “Chaikovites "actually led.

The mass “going to the people” of 1874 was unprecedented in the Russian liberation movement in terms of the scale and enthusiasm of the participants. It covered more than 50 provinces, from the Far North to Transcaucasia and from the Baltic states to Siberia. All the revolutionary forces of the country went to the people at the same time - approximately 2-3 thousand active figures (99% boys and girls), who were helped by twice or three times as many sympathizers. Almost all of them believed in the revolutionary receptivity of the peasants and in an imminent uprising: the Lavrists expected it in 2-3 years, and the Bakuninists - “in the spring” or “in the autumn.”

The receptivity of the peasants to the calls of the populists, however, turned out to be less than expected not only by the Bakuninists, but also by the Lavrists. The peasants showed particular indifference to the fiery tirades of the populists about socialism and universal equality. “What’s wrong, brother, you say,” an elderly peasant declared to the young populist, “look at your hand: it has five fingers and all are unequal!” There were also big misfortunes. “A friend and I were walking along the road,” said S.M. Kravchinsky.- A man is catching up with us on the firewood. I began to explain to him that taxes should not be paid, that officials were robbing the people, and that according to the scripture, it was necessary to rebel. The man whipped the horse, but we also increased our pace. He started the horse jogging, but we ran after him, and all the time I continued to explain to him about taxes and rebellion. Finally, the man started his horse to gallop, but the horse was crappy, so we kept up with the sleigh and preached to the peasant until we were completely out of breath.”

The authorities, instead of taking into account the loyalty of the peasants and subjecting the exalted populist youth to moderate punishments, attacked “going to the people” with the most severe repressions. All of Russia was swept by an unprecedented wave of arrests, the victims of which were, /255/ according to an informed contemporary, 8 thousand people in the summer of 1874 alone. They were kept in pre-trial detention for three years, after which the most “dangerous” of them were brought before the OPPS court.

The trial in the case of “going to the people” (the so-called “Trial of the 193s”) took place in October 1877 - January 1878. and turned out to be the largest political process in the entire history of tsarist Russia. The judges handed down 28 convict sentences, more than 70 exile and prison sentences, but acquitted almost half of the accused (90 people). Alexander II, however, with his authority sent into exile 80 of the 90 acquitted by the court.

The “going to the people” of 1874 did not so much excite the peasants as it frightened the government. An important (albeit side) result was the fall of P.A. Shuvalova. In the summer of 1874, in the midst of the “walk,” when the futility of eight years of Shuvalov’s inquisition became obvious, the tsar demoted “Peter IV” from dictator to diplomat, telling him among other things: “You know, I appointed you ambassador to London.”

For the populists, Shuvalov's resignation was little consolation. The year 1874 showed that the peasantry in Russia does not yet have an interest in the revolution, socialist in particular. But the revolutionaries did not want to believe it. They saw the reasons for their failure in the abstract, “bookish” nature of propaganda and in the organizational weakness of “the movement,” as well as in government repression, and with colossal energy they set about eliminating these reasons.

The very first populist organization that arose after the “walk among the people” in 1874 (the All-Russian Social Revolutionary Organization or the “Muscovites’ Circle”) showed concern for the principles of centralism, secrecy and discipline, which was unusual for the participants in the “walk,” and even adopted a charter. “Circle of Muscovites” is the first association of populists of the 70s, armed with a charter. Taking into account the sad experience of 1874, when the Narodniks failed to gain the trust of the people, the “Muscovites” expanded the social composition of the organization: along with the “intellectuals,” they accepted into the organization a workers’ circle led by Pyotr Alekseev. Unexpectedly for other populists, the “Muscovites” concentrated their activities not in the peasant environment, but in the working class, because, under the impression of government repressions of 1874, they retreated before the difficulties of direct propaganda among the peasants and returned to what the populists were doing before 1874, i.e. e. to prepare workers as intermediaries between the intelligentsia and the peasantry. /256/

The “Circle of Muscovites” did not last long. It took shape in February 1875, and two months later it was destroyed. Pyotr Alekseev and Sophia Bardina spoke on his behalf at the trial of the “50” in March 1877 with programmatic revolutionary speeches. Thus, for the first time in Russia, the dock was turned into a revolutionary platform. The circle died, but its organizational experience, along with the organizational experience of the Great Propaganda Society, was used by the Land and Freedom society.

By the fall of 1876, the populists created a centralized organization of all-Russian significance, calling it “Land and Freedom” - in memory of its predecessor, “Land and Freedom” in the early 60s. The second “Land and Freedom” was intended not only to ensure reliable coordination of revolutionary forces and protect them from government repression, but also to fundamentally change the nature of propaganda. The landowners decided to rouse the peasantry to fight not under the “bookish” and alien banner of socialism, but under slogans emanating from the peasantry themselves - first of all, under the slogan of “land and freedom,” all the land and full freedom.

Like the populists of the first half of the 70s, the landowners still remained anarchists, but less consistent. They only declared in their program: “ Finite our political and economic ideal is anarchy and collectivism”; They narrowed the specific demands “to those that are actually feasible in the near future”: 1) the transfer of all land into the hands of the peasants, 2) complete communal self-government, 3) freedom of religion, 4) self-determination of the nations living in Russia, up to their separation. The program did not set purely political goals. The means to achieve the goal were divided into two parts: organizational(propaganda and agitation among peasants, workers, intelligentsia, officers, even among religious sects and “robber gangs”) and disorganizing(here, in response to the repressions of 1874, for the first time the populists legalized individual terror against the pillars and agents of the government).

Along with the “Land and Freedom” program, it adopted a charter imbued with the spirit of centralism, strict discipline and secrecy. The society had a clear organizational structure: Society Council; the main circle, divided into 7 special groups by type of activity; local groups in at least 15 major cities of the empire, including Moscow, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Samara, Voronezh, Saratov, Rostov, Kyiv, Kharkov, Odessa. “Land and Freedom” 1876-1879 – the first revolutionary organization in Russia that began to publish its own literary organ, the newspaper “Land and Freedom”. For the first time, she managed to introduce her agent (N.V. Kletochnikov) into the holy of holies of the royal investigation - into the III department. The composition of “Land and Freedom” hardly exceeded 200 people, but relied on a wide /257/ circle of sympathizers and contributors in all layers of Russian society.

The organizers of “Land and Freedom” were the “Chaikovites”, the spouses of M.A. and O.A. Nathanson: The landowners called Mark Andreevich the head of society, Olga Alexandrovna - its heart. Together with them, and especially after their quick arrest, technology student Alexander Dmitrievich Mikhailov, one of the best organizers among the populists, emerged as the leader of “Land and Freedom” (in this regard, only M.A. Nathanson and A. .I. Zhelyabov) and the most outstanding of them (there is no one to put on a par with him) conspirator, a classic of revolutionary conspiracy. Like none of the landowners, he delved into literally every business of society, set everything up, set everything in motion, protected everything. The Zemlyovoltsy called Mikhailov “Cato the Censor” of the organization, its “shield” and “armor”, and considered him a ready prime minister in the event of a revolution; in the meantime, for his constant concern for order in the revolutionary underground, they gave him the nickname “Janitor” - with which he went down in history: Mikhailov the Janitor.

The main circle of “Land and Freedom” included other outstanding revolutionaries, including Sergei Mikhailovich Kravchinsky, who later became a world-famous writer under the pseudonym “Stepnyak”; Dmitry Andreevich Lizogub, who was known in radical circles as a “saint” (L.N. Tolstoy portrayed him in the story “Divine and Human” under the name Svetlogub); Valerian Andreevich Osinsky is an extremely charming favorite of “Land and Freedom”, “Apollo of the Russian Revolution”, according to Kravchinsky; Georgy Valentinovich Plekhanov - later the first Russian Marxist; future leaders of “Narodnaya Volya” A.I. Zhelyabov, S.L. Perovskaya, N.A. Morozov, V.N. Figner.

“Land and Freedom” sent most of its forces to organize village settlements. The landowners considered (quite rightly) the “wandering” propaganda of 1874 useless and switched to settled propaganda among the peasants, creating permanent settlements of revolutionary propagandists in the villages under the guise of teachers, clerks, paramedics, etc. The largest of these settlements were two in Saratov in 1877 and 1878-1879, where A.D. was active. Mikhailov, O.A. Nathanson, G.V. Plekhanov, V.N. Figner, N.A. Morozov and others.

However, village settlements were also not successful. The peasants showed no more revolutionary spirit before the settled propagandists than they did before the “wandering” propagandists. The authorities caught sedentary propagandists no less successfully than “vagrant” ones, in many respects. The American journalist George Kennan, who was studying Russia at that time, testified that the populists who got jobs as clerks were “soon arrested, concluding that they were revolutionary from the fact that they did not drink /258/ and did not take bribes” (it was immediately clear that the clerks were not real).

Discouraged by the failure of their settlements, the populists undertook a new revision of tactics after 1874. Then they explained their fiasco by shortcomings in the nature and organization of propaganda and (in part!) by government repression. Now, having eliminated obvious shortcomings in the organization and nature of propaganda, but again having failed, they considered it the main reason for government repression. This suggests a conclusion: it is necessary to concentrate efforts on the fight against the government, i.e. already on political struggle.

Objectively, the revolutionary struggle of the populists always had a political character, since it was directed against the existing system, including its political regime. But, without highlighting particularly political demands, focusing on social propaganda among the peasants, the populists directed the spearhead of their revolutionary spirit, as it were, past the government. Now, having elected the government as target No. 1, the landowners brought the disruptive part, which initially remained in reserve, to the forefront. The propaganda and agitation of “Land and Freedom” became politically acute, and in parallel with them, terrorist acts began to be undertaken against the authorities.

On January 24, 1878, a young teacher Vera Zasulich shot at the St. Petersburg mayor F.F. Trepov (adjutant general and personal friend of Alexander II) and seriously wounded him because, on his orders, a political prisoner, landowner A.S., was subjected to corporal punishment. Emelyanov. On August 4 of the same year, the editor of Land and Freedom, Sergei Kravchinsky, committed an even more high-profile terrorist act: in broad daylight, in front of the Tsar’s Mikhailovsky Palace in St. Petersburg (now the Russian Museum), he stabbed to death the chief of gendarmes N.V. Mezentsov, personally responsible for the mass repressions against the populists. Zasulich was captured at the scene of the assassination attempt and put on trial; Kravchinsky fled.

The Narodniks' turn to terror met with undisguised approval among wide circles of Russian society, intimidated by government repressions. This was demonstrated firsthand by the public trial of Vera Zasulich. The trial revealed such flagrant abuses of power on the part of Trepov that the jury found it possible to acquit the terrorist. The audience applauded Zasulich’s words: “It’s hard to raise your hand against a person, but I had to do it.” The acquittal in the Zasulich case caused a real sensation not only in Russia, but also abroad. Since it was passed on March 31, 1878, and the newspapers reported on it on April 1, many perceived it as an April Fool's joke, and then the whole country fell, in the words of /259/ P.L. Lavrov, into “liberal intoxication.” The revolutionary spirit was growing everywhere and fighting spirit was in full swing - especially among students and workers. All this stimulated the political activity of the Zemlya Volyas and encouraged them to commit new terrorist acts.

Growing, the “red” terror of “Land and Freedom” fatally pushed it towards regicide. “It became strange,” recalled Vera Figner, “to beat the servants who did the will of the one who sent them, and not touch the master.” On the morning of April 2, 1879, landowner A.K. Solovyov entered with a revolver onto Palace Square, where Alexander II was walking accompanied by guards, and managed to unload the entire clip of five cartridges at the Tsar, but only shot through the Tsar’s overcoat. Captured immediately by guards, Soloviev was soon hanged.

Some of the landowners, led by Plekhanov, rejected terror, advocating for the previous methods of propaganda in the countryside. Therefore, the terrorist acts of Zasulich, Kravchinsky, Solovyov caused a crisis in “Land and Freedom”: two factions emerged in it – “politicians” (mainly terrorists) and “villagers”. In order to prevent a split in society, it was decided to convene a congress of landowners. It took place in Voronezh on June 18-24, 1879.

The day before, June 15-17, “politicians” gathered factionally in Lipetsk and agreed on their amendment to the “Land and Freedom” program. The meaning of the amendment was to recognize the necessity and priority of the political struggle against the government, because “no public activity aimed at the benefit of the people is impossible due to the arbitrariness and violence reigning in Russia.” The “politicians” made this amendment at the Voronezh Congress, where it became clear, however, that both factions did not want a split, hoping to conquer society from within. Therefore, the congress adopted a compromise resolution that allowed for the combination of apolitical propaganda in the countryside with political terror.

This solution could not satisfy either side. Very soon, both “politicians” and “villages” realized that it was impossible to “combine kvass and alcohol”, that a split was inevitable, and on August 15, 1879, they agreed to divide “Land and Freedom” into two organizations: “People’s Will” and “Black redistribution." It was divided, as N.A. aptly put it. Morozov, and the very name of “Land and Freedom”: the “villagers” took for themselves “ land", and "politicians" - " will", and each faction went its own way. /260/

The people to whom there was a “walk”

Walking among the people is an attempt by revolutionary-minded youth of the 60-70s of the 19th century to involve peasants in their movement, to make them like-minded people. Naive, beautiful-hearted, exalted, ignorant of life, students, students, young nobles and commoners, who had read Bakunin, Lavrov, Herzen, Chernyshevsky, believed in the imminent arrival of revolution in Russia and went to the villages in order to hastily prepare the people for it.“Young Petersburg was in full swing in the literal sense of the word and lived an intense life, fueled by great expectations. Everyone was gripped by an unbearable thirst to renounce the old world and dissolve in the national element in the name of its liberation. People had boundless faith in their great mission, and it was useless to challenge this faith. It was a kind of purely religious ecstasy, where reason and sober thought no longer had a place. And this general excitement grew continuously until the spring of 1874, when a real, truly crusade to the Russian countryside began from almost all cities and towns...” (from the memoirs of populist N.A. Charushin)

“To the people! To the people! - There were no dissenters here. Everyone also agreed that before going “to the people,” you need to acquire skills for physical labor and master some kind of craft specialty, be able to turn into a working person, an artisan. This gave birth to a craze for organizing all kinds of (carpentry, shoemaking, blacksmithing, etc.) workshops, which in the autumn of 1873, like mushrooms after rain, began to grow throughout Russia; “The passion for this idea reached the point that those who wanted to complete their education, even in the 3rd or 4th year, were directly called traitors to the people, scoundrels. The school was abandoned, and workshops began to grow in its place” (Frolenko M. F. Collected works in 2 volumes. M., 1932. T. 1. P. 200)

The beginning of the mass “Walk to the People” - spring 1874

Everyone who went “to the people” settled, as a rule, one or two at a time with relatives and friends (most often in landowners’ estates and in the apartments of teachers, doctors, etc.), or in special propaganda “points” , mainly workshops that were created everywhere. Having settled in one place or another as teachers, clerks, zemstvo doctors, thus trying to become closer to the peasants, young people spoke at meetings, talked with peasants, trying to instill distrust in the authorities, called for not paying taxes, not obeying the administration, and explained the injustice of land distribution . Refuting centuries of popular ideas that royal power was from God, the populists also tried to promote atheism.

“by rail from the centers to the provinces. Each young man could find in his pocket or behind his boot a false passport in the name of some peasant or tradesman, and in his bundle - an undershirt or, in general, peasant clothing, if it was not already on the shoulders of the passenger, and several revolutionary books and pamphlets "(from the memoirs of populist S. F. Kovalik)

Revolutionary propaganda in 1874 covered 51 provinces of the Russian Empire. The total number of its active participants amounted to approximately two to three thousand people, and twice or three times as many sympathized with them and helped them in every possible way.

The result of “Walking among the People”

The event ended disastrously. The peasants turned out to be completely different from what their intellectual imagination had pictured.

They still responded to conversations about the severity of taxes, the unfair distribution of land, the “evil” landowner, but the tsar was still a “father,” the Orthodox faith was a saint, the words “socialism, revolution” were incomprehensible, and the propagandists, no matter how hard they tried, strange, strangers, gentlemen, white-handed ones. So, when the state became interested in participants in the “going to the people”, it was the peasants who handed over some of the agitators to the police

By the end of 1874, the authorities had caught the overwhelming majority of the populists. Many were sent to remote provinces under police supervision. Others were imprisoned.

Total number of arrested: about a thousand, over one and a half thousand, 1600 people. Such figures were given by P. L. Lavrov and S. M. Kravchinsky. But the publicist V.L. Burtsev lists 3500, the populist M.P. Sazhin - 4000. It is this information that agrees better than others with such an authoritative source as the senior assistant to the head of the Moscow provincial gendarme department I.L. Slezkin V.D. Novitsky , which carried out a “check of the number of all arrested persons in 26 provinces” and counted more than 4 thousand people under arrest in 1874. But arrests then took place not in 26, but in 37 provinces. Therefore, Novitsky’s figure cannot be considered exhaustive (N. Troitsky “History of Russia in the 18th-19th centuries”)

From October 18, 1877 to January 23, 1878, the “case of revolutionary propaganda in the empire” was heard in St. Petersburg, which received in history the name “trial of 193” (in total, charges were brought against 265 people, but by the beginning of the trial, 43 of them died, 12 - committed suicide and 38 - went crazy) The defendants were members of at least 30 different propaganda circles and almost all were accused of organizing a single “criminal community” with the goal of a coup d’etat and “cutting off all officials and wealthy people.” The court, however, handed down a lenient sentence, not at all what the government was counting on: only 28 were sentenced to hard labor.

“on the one hand, the enormity of forces, endless selflessness, heroism in leaders; on the other hand, the results are completely insignificant... We left behind several dozen propagandists from the people, that’s all the immediate benefit we brought! But 800 people will be sued and at least 400 of them will die forever. This means that 10 or 20 people died to leave only one behind! There is nothing to say, a profitable exchange, a successful fight, a wonderful path” (from the memoirs of Stepnyak-Kravchinsky)

Reasons for the failure of “going to the people”

The populists mistakenly viewed the peasantry as a force capable of carrying out a socialist revolution, naively believed “in the communist instincts of the peasant” and in his “revolutionary spirit”, imagined an “ideal peasant”, ready to abandon his land, home, family and take an ax at their first call in order to go against the landowners and the tsar, but in reality they encountered a dark, downtrodden and infinitely oppressed person.

The fallacy and utopianism of populist ideas about the peasantry was most often explained by the fact that they were built on abstract, theoretical conclusions that had nothing in common with life. As a result, the populists became disillusioned with the mood of the people, and the people, for their part, did not understand them.

Walking among the people- a movement of student youth and revolutionaries - populists with the goal of educating the people and revolutionary agitation directly among the peasant masses. The first, student and educational stage began in 1861, and the movement reached its greatest scope in the form of organized revolutionary agitation in 1874. “Going to the people” influenced the self-organization of the revolutionary movement, but did not have a significant impact on the masses. This phrase has entered the Russian language and is used ironically today.

Encyclopedic YouTube

1 / 3

Intelligence interrogation: Pavel Peretz about the rise of the intelligentsia among the people

Revolutionary movement in Russia on Tue. floor. XIX century Narodnaya Volya.

Bank scam exposed! (Part 3) Ruble code 810 RUR or 643 RUB?! Analysis of lies of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation

First stage

In the mid-19th century, interest in higher education, especially in the natural sciences, grew in Russia. But in the fall of 1861, the government raised tuition fees and banned student mutual aid funds. In response to this, student unrest occurred at universities, after which many students were expelled from educational institutions. A significant part of active youth found themselves thrown out of life - expelled students could neither get a job in the civil service due to “unreliability” nor continue their studies. Herzen wrote in the newspaper “Bell” in 1861:

In subsequent years, the number of “exiles from science” grew, and going to the people became a mass phenomenon. During this period, former and failed students became rural teachers and paramedics.

The propaganda activities of the revolutionary Zaichnevsky, the author of the proclamation “Young Russia”, who went to the people back in 1861, became very famous. However, in general during this period the movement had a social and educational character of “serving the people,” and Zaichnevsky’s radical Jacobin agitation was rather an exception.

Second phase

In the early 1870s, the populists set the task of involving the people in the revolutionary struggle. The ideological leaders of the organized revolutionary movement among the people were the populist N. V. Tchaikovsky, the anarchist P. A. Kropotkin, the “moderate” revolutionary theorist P. L. Lavrov and the radical anarchist M. A. Bakunin, who wrote:

A theoretical view of this problem was developed by the illegal magazine “Forward! ", published since 1873 under the editorship of Lavrov. However, the revolutionary youth sought immediate action, and a radicalization of views took place in the spirit of the ideas of the anarchist Bakunin. Kropotkin developed a theory according to which, in order to carry out the revolution, the advanced intelligentsia must live the life of the people and create circles of active peasants in the villages, followed by their unification into the peasant movement. Kropotkin's teachings combined Lavrov's ideas about enlightening the masses and the anarchist ideas of Bakunin, who denied the political struggle within the institutions of the state, the state itself, and called for a nationwide revolt.

In the early 70s, there were many cases of individual revolutionaries going to the people. For example, Kravchinsky agitated the peasants of the Tula and Tver provinces back in the fall of 1873 with the help of the Gospel, from which he drew socialist conclusions. Propaganda in the crowded huts continued long after midnight and was accompanied by the singing of revolutionary anthems. But the Narodniks had developed a general view of the need for mass outreach to the people by 1874. The mass action began in the spring of 1874, was associated with a social upsurge, remained largely spontaneous and involved different categories of people. A significant part of the youth was inspired by Bakunin's idea to immediately start a revolt, but due to the diversity of the participants, the propaganda was also varied, from calls for an immediate uprising to modest tasks of educating the people. The movement covered about forty provinces, mainly in the Volga region and southern Russia. It was decided to launch propaganda in these regions in connection with the famine of 1873-1874 in the Middle Volga region; the populists also believed that the traditions of Razin and Pugachev were alive here.

In practice, going to the people looked like this: young people, usually students, one at a time or in small groups under the guise of trade intermediaries, craftsmen, etc., moved from village to village, speaking at meetings, talking with peasants, trying to instill distrust in the authorities , called on people not to pay taxes, not to obey the administration, and explained the injustice of land distribution after the reform. Proclamations were distributed among literate peasants. Refuting the well-established opinion among the people that the royal power was from God, the populists initially propagated Earth and will decided to change tactics and announced a “second visit to the people.” It was decided to move from the unsuccessful practice of “flying squads” to organizing permanent settlements of agitators. Revolutionaries opened workshops in villages, got jobs as teachers or doctors, and tried to create revolutionary cells. However, the experience of three years of agitation showed that the peasantry did not accept either radical revolutionary and socialist calls, or explanations of the current needs of the people, as the populists understood them. Attempts to rouse the people to fight did not bring any serious results, and the government paid attention to the revolutionary propaganda of the populists and launched repressions. Many propagandists were handed over to the authorities by the peasants themselves. More than 4 thousand people were arrested. Of these, 770 propagandists were involved in the inquiry, and 193 people were brought to trial in 1877. However, only 99 defendants were sentenced to hard labor, prison and exile; the rest were either given pre-trial detention or were completely acquitted.

The futility of revolutionary propaganda among the people, mass arrests, the trial of the 193s and the trial of the fifty in 1877-1788 put an end to the movement.

Populism is an ideological movement of a radical nature that opposed serfdom, for the overthrow of the autocracy or for the global reform of the Russian Empire. As a result of the actions of populism, Alexander 2 was killed, after which the organization actually disintegrated. Neo-populism was restored in the late 1890s in the form of the activities of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

Main dates:

- 1874-1875 – “the movement of populism among the people.”

- 1876 – creation of “Land and Freedom”.

- 1879 – “Land and Freedom” splits into “People’s Will” and “Black Redistribution”.

- March 1, 1881 – murder of Alexander 2.

Prominent historical figures of populism:

- Bakunin Mikhail Aleksandrovich is one of the key ideologists of populism in Russia.

- Lavrov Petr Lavrovich - scientist. He also acted as an ideologist of populism.

- Chernyshevsky Nikolai Gavrilovich - writer and public figure. The ideologist of populism and the speaker of its basic ideas.

- Zhelyabov Andrey Ivanovich - was part of the management of “Narodnaya Volya”, one of the organizers of the assassination attempt on Alexander 2.

- Nechaev Sergei Gennadievich - author of the "Catechism of a Revolutionary", an active revolutionary.

- Tkachev Petr Nikolaevich is an active revolutionary, one of the ideologists of the movement.

The ideology of revolutionary populism

Revolutionary populism in Russia originated in the 60s of the 19th century. Initially it was called not “populism”, but “public socialism”. The author of this theory was A.I. Herzen N.G. Chernyshevsky.

Russia has a unique chance to transition to socialism, bypassing capitalism. The main element of the transition should be the peasant community with its elements of collective land use. In this sense, Russia should become an example for the rest of the world.

Herzen A.I.

Why is Populism called revolutionary? Because it called for the overthrow of the autocracy by any means, including through terror. Today, some historians say that this was the innovation of the populists, but this is not so. The same Herzen, in his idea of “public socialism,” said that terror and revolution are one of the methods of achieving the goal (albeit an extreme method).

Ideological trends of populism in the 70s

In the 70s, populism entered a new stage, when the organization was actually divided into 3 different ideological movements. These movements had a common goal - the overthrow of the autocracy, but the methods of achieving this goal differed.

Ideological currents of populism:

- Propaganda. Ideologist – P.L. Lavrov. The main idea is that historical processes should be led by thinking people. Therefore, populism must go to the people and enlighten them.

- Rebellious. Ideologist – M.A. Bakunin. The main idea was that propaganda ideas were supported. The difference is that Bakunin spoke not simply about enlightening the people, but about calling them to take up arms against their oppressors.

- Conspiratorial. Ideologist – P.N. Tkachev. The main idea is that the monarchy in Russia is weak. Therefore, there is no need to work with the people, but to create a secret organization that will carry out a coup and seize power.

All directions developed in parallel.

Joining the People is a mass movement that began in 1874, in which thousands of young people in Russia took part. In fact, they implemented the ideology of Lavrov and Bakunin’s populism, conducting propaganda with village residents. They moved from one village to another, distributed propaganda materials to people, talked with people, calling them to take active action, explaining that they could not continue to live like this. For greater persuasiveness, entering the people presupposed the use of peasant clothing and conversation in a language understandable to the peasants. But this ideology was greeted with suspicion by the peasants. They were wary of strangers who spoke “terrible speeches,” and also thought completely differently from the representatives of populism. Here, for example, is one of the documented conversations:

- “Who owns the land? Isn’t she God’s?” - says Morozov, one of the active participants in joining the people.

- “It’s God’s where no one lives. And where people live is human land,” was the peasants’ answer.

It is obvious that populism had difficulty imagining the way of thinking of ordinary people, and therefore their propaganda was extremely ineffective. Largely because of this, by the fall of 1874, “entering the people” began to fade away. By this time, repressions by the Russian government began against those who “walked.”

In 1876, the organization “Land and Freedom” was created. It was a secret organization that pursued one goal - the establishment of the Republic. The peasant war was chosen to achieve this goal. Therefore, starting from 1876, the main efforts of populism were directed towards preparing for this war. The following areas were chosen for preparation:

- Propaganda. Again the members of “Land and Freedom” addressed the people. They found jobs as teachers, doctors, paramedics, and minor officials. In these positions, they agitated the people for war, following the example of Razin and Pugachev. But once again, the propaganda of populism among the peasants did not produce any effect. The peasants did not believe these people.

- Individual terror. In fact, we are talking about disorganization work, in which terror was carried out against prominent and capable statesmen. By the spring of 1879, as a result of terror, the head of the gendarmes N.V. Mezentsev and Governor of Kharkov D.N. Kropotkin. In addition, an unsuccessful attempt was made on Alexander 2.

By the summer of 1879, “Land and Freedom” split into two organizations: “Black Redistribution” and “People’s Will”. This was preceded by a congress of populists in St. Petersburg, Voronezh and Lipetsk.

Black redistribution

The “black redistribution” was headed by G.V. Plekhanov. He called for an abandonment of terror and a return to propaganda. The idea was that the peasants were simply not yet ready for the information that populism brought upon them, but soon the peasants would begin to understand everything and “take up their pitchforks” themselves.

People's will

“Narodnaya Volya” was controlled by A.I. Zhelyabov, A.D. Mikhailov, S.L. Petrovskaya. They also called for the active use of terror as a method of political struggle. Their goal was clear - the Russian Tsar, who began to be hunted from 1879 to 1881 (8 attempts). For example, this led to the assassination attempt on Alexander 2 in Ukraine. The king survived, but 60 people died.

The end of the activities of populism and brief results

As a result of the assassination attempts on the emperor, unrest began among the people. In this situation, Alexander 2 created a special commission, headed by M.T. Loris-Melikov. This man intensified the fight against populism and its terror, and also proposed a draft law whereby certain elements of local government could be transferred under the control of “electors.” In fact, this was what the peasants demanded, which means this step significantly strengthened the monarchy. This draft law was to be signed by Alexander 2 on March 4, 1881. But on March 1, the populists committed another terrorist act, killing the emperor.

Alexander 3 came to power. “Narodnaya Volya” was closed, the entire leadership was arrested and executed by court verdict. The terror that the Narodnaya Volya unleashed was not perceived by the population as an element of the struggle for the liberation of the peasants. In fact, we are talking about the meanness of this organization, which set itself high and correct goals, but to achieve them chose the most vile and base opportunities.

In the early 70s of the XIX century. Russian revolutionaries stood at a crossroads.

Spontaneous peasant uprisings that broke out in many provinces in response to the reform of 1861 were suppressed by police and troops. The revolutionaries failed to implement the plan for a general peasant uprising planned for 1863. N. G. Chernyshevsky (see article “Contemporary”. N. G. Chernyshevsky and N. A. Dobrolyubov”) languished in hard labor; his closest associates, who formed the center of the revolutionary organization, were arrested, some died or also ended up in hard labor. In 1867, A. I. Herzen’s “Bell” fell silent.

During this difficult time, the young generation of revolutionaries was looking for new forms of struggle against tsarism, new ways to awaken the people and attract them to their side. The youth decided to go “to the people” and, together with enlightenment, spread the ideas of revolution among the dark peasantry, overwhelmed by poverty and lack of rights. Hence the name of these revolutionaries - populists.

In the spring and summer of 1874, young people, most often students, commoners or nobles, hastily mastered one or another profession useful for peasants and dressed in peasant clothes, “went among the people.” Here is how a contemporary tells about the mood that gripped the progressive youth: “Go, at all costs, go, but be sure to wear an overcoat, a sundress, simple boots, even bast shoes... Some dreamed of a revolution, others simply wanted to watch - and spread throughout Russia as artisans, peddlers, and were hired for field work; it was assumed that the revolution would occur no later than three years later - this was the opinion of many.”

From St. Petersburg and Moscow, where at that time there were the largest number of students, the revolutionaries moved to the Volga. There, in their opinion, memories of the peasant uprisings led by Razin and Pugachev were still alive among the people. A smaller part went to Ukraine, to the Kyiv, Podolsk and Yekaterinoslav provinces. Many went to their homeland or to places where they had some connections.

Devoting their lives to the people, striving to become closer to them, the populists wanted to live their lives. They ate extremely poorly, sometimes slept on bare boards, and limited their needs to the essentials. “We had a question,” wrote one of the participants in the “walk among the people,” “is it permissible for us, who have taken the pilgrim’s staff in our hands... to eat herrings?! For sleeping, I bought myself matting at the market, which was already in use, and put it on the plank bunks.

The old washcloth soon rubbed through, and we had to sleep on bare boards.” One of the outstanding populists of that time, P.I. Voinaralsky, a former justice of the peace, who gave his entire fortune to the cause of the revolution, opened a shoemaker's workshop in Saratov. It trained populists who wanted to go to the villages as shoemakers, and stored forbidden literature, seals, passports - everything necessary for the illegal work of revolutionaries. Voinaralsky organized a network of shops and inns in the Volga region that served as strongholds for revolutionaries.

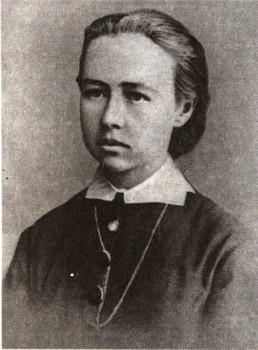

Vera Figner. Photograph from the 1870s.

One of the most heroic female revolutionaries, Sofya Perovskaya, having completed courses for rural teachers, in 1872 went to the Samara province, to the village of the Turgenev landowners. Here she began inoculating peasants with smallpox. At the same time, she became acquainted with their lives. Having moved to the village of Edimnovo, Tver province, Perovskaya became an assistant to a public school teacher; here she also treated peasants and tried to explain to them the reasons for the plight of the people.

Dmitry Rogachev. Photograph from the 1870s.

Another remarkable revolutionary, Vera Figner, paints a vivid picture of work in the village, although dating back to a later time, in her memoirs. Together with her sister Evgenia, in the spring of 1878, she arrived in the village of Vyazmino, Saratov province. The sisters began by organizing an outpatient clinic. The peasants, who had never seen not only medical care, but also human treatment of themselves, were literally besieged by them. Within a month, Vera received 800 patients. Then the sisters managed to open a school. Evgenia told the peasants that she would undertake to teach their children for free, and she gathered 29 girls and boys. There were no schools in Vyazmino or in the surrounding villages at that time. Some students were brought twenty miles away. Adult men also came to learn literacy and especially arithmetic. Soon the peasants called Evgenia Figner nothing more than “our golden teacher.”

After finishing their classes at the pharmacy and school, the sisters took books and went to one of the peasants. In the house where they spent their evenings, relatives and neighbors of the owners gathered and listened to readings until late in the evening. They read Lermontov, Nekrasov, Saltykov-Shchedrin and other writers. Conversations often arose about the difficult life of a peasant, about the land, about the attitude towards the landowner and the authorities. Why did hundreds of young men and women go to the village, to the peasants?

The revolutionaries of those years saw the people only in the peasantry. The worker in their eyes was the same peasant, only temporarily torn off from the land. The populists were convinced that peasant Russia could bypass the capitalist path of development, which was painful for the people.

Arrest of a propagandist. Painting by I.V. Repin.

The rural community seemed to them the basis for establishing a fair social system. They hoped to use it to transition to socialism, bypassing capitalism.

The populists conducted revolutionary propaganda in 37 provinces. The Minister of Justice wrote at the end of 1874 that they managed to “cover more than half of Russia with a network of revolutionary circles and individual agents.”

Some populists went “to the people,” hoping to quickly organize the peasants and rouse them to revolt, others dreamed of launching propaganda in order to gradually prepare for the revolution, while others only wanted to educate the peasants. But they all believed that the peasant was ready to rise to revolution. Examples of past uprisings led by Bolotnikov, Razin and Pugachev, the scope of the peasant struggle during the period of the abolition of serfdom supported this belief among the populists.

How did the peasants greet the populists? Did these revolutionaries find a common language with the people? Did they manage to rouse the peasants to revolt or at least prepare them for it? No. Hopes to rouse the peasants to revolution did not materialize. Participants in the “going to the people” were only able to successfully treat peasants and teach them to read and write.

Sofia Perovskaya

The populists imagined an “ideal man”, ready to leave his land, home, family and take an ax at their first call in order to go against the landowners and the tsar, but in reality they were faced with a dark, downtrodden and infinitely oppressed man. The peasant believed that all the burden of his life came from the landowner, but not from the tsar. He believed that the king was his father and protector. The man was ready to talk about the severity of taxes, but it was impossible to talk with him about the overthrow of the Tsar and the social revolution in Russia at that time.

The brilliant propagandist Dmitry Rogachev traveled across half of Russia. Possessing great physical strength, he pulled the strap with barge haulers on the Volga. Everywhere he tried to conduct propaganda, but could not captivate a single peasant with his ideas.

By the end of 1874, the government had arrested over a thousand populists. Many were sent to remote provinces without trial under police supervision. Others were imprisoned.

On October 18, 1877, in the Special Presence of the Senate (the highest judicial body), the “case of revolutionary propaganda in the empire” began to be heard, which in history became known as the “trial of the 193s.” One of the most prominent populist revolutionaries, Ippolit Myshkin, gave a brilliant speech at the trial. He openly called for a general popular uprising and said that revolution could only be carried out by the people themselves.

Realizing the futility of propaganda in the countryside, the revolutionaries moved on to other methods of fighting tsarism, although some of them also tried to get closer to the peasantry. The majority moved on to direct political struggle against the autocracy for democratic freedoms. One of the main means of this struggle was terror - the murder of individual representatives of the tsarist government and the tsar himself.

The tactics of individual terror prevented the awakening of the broad masses of the people to the revolutionary struggle. A new one took the place of the murdered tsar or dignitary, and even more severe repressions fell on the revolutionaries (see article “March 1, 1881”). While performing heroic deeds, the populists were never able to find a way to the people in whose name they gave their lives. This is the tragedy of revolutionary populism. And yet, the populism of the 70s played an important role in the development of the Russian revolutionary movement. V.I. Lenin highly valued the populist revolutionaries for trying to awaken the masses to a conscious revolutionary struggle, calling on the people to revolt and overthrow the autocracy.