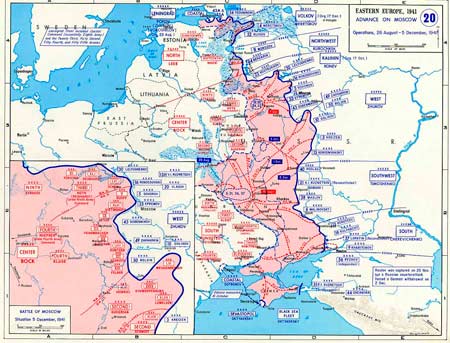

The Battle of Moscow, which began in September 1941, was one of the bloodiest battles of times. In three months, the troops of Nazi Germany managed to come close to the capital. The operation to capture the city was called “Typhoon”, which began on September 30.

The first stage of the battle for Moscow 09/30/1941 - 12/5/1941 was defensive in nature. The second stage 12/5/1941 - 04/20/1942 was a counter-offensive of the Soviet Army, and from January 1942 a powerful offensive against the enemy.

On October 19, 1941, the city was placed under siege. The battle for Moscow was in full swing. The enemy offensive was stopped on October 30. Germany planned to take the capital by November 7th. On this day, starting in 1918, the USSR celebrated.

There was a great battle near Moscow. The city was defended by three fronts, but the number of German forces was still greater. The Germans had a quarter more people, twice as many tanks and artillery, and twice as many planes.

Some of the defenders of Moscow, on the distant approaches to it, were surrounded and defeated near Vyazma. The second line of defense in the Mozhaisk area was able to hold out for several days. The situation was critical.

Georgy Konstantinovich was entrusted with leading the defense of the city. After taking command, Zhukov united the three defense fronts into one - the Western.

From the east, troops from Siberia and the Far East were drawn up to the besieged city. It was necessary to hold on with all one's might until reinforcements arrived. To defend the capital, 50 thousand Muscovites went to the front as volunteers, who joined the ranks of the people's militia and the Red Army.

On November 7, a parade of Soviet troops took place on Red Square; Marshal Budyonny hosted the parade. After the parade, the soldiers immediately went to the front. Meanwhile, the Germans were getting closer and closer... German troops approached Moscow to a distance of 30 kilometers. Hitler hurried his generals, calling for them to capture the city as quickly as possible.

The resilience of the Russian man, his courage, bravery, strength and desire for self-sacrifice for the good of the Motherland did not allow the Germans to carry out their insidious plans. The Battle of Moscow is covered in human feats of people of completely different ranks and titles.

In December there was a turning point in the Battle. Russian troops went on the offensive and, with the support of aviation, somewhat pushed the Germans away from the city. The Germans fled, abandoning their military equipment. The Soviet government sent skiers, paratroopers and cavalrymen to the rear of those fleeing, who inflicted great damage on the Germans. On January 3, Hitler ordered his generals to cling to every meter of ground, to hold on until the last ammunition. The order was not carried out.

In the battle of Moscow, the Germans lost 500 thousand soldiers, 1.5 thousand tanks, 2,500 guns, 15 thousand vehicles. The losses of the Red Army were comparable... In the Battle of Moscow, Russian soldiers managed to defeat the large German group of troops "Center" and force the enemy to retreat several hundred kilometers from Moscow. The victory near Moscow also had a psychological significance. The myth about the invincibility of the German combat vehicle was dispelled. After the victory in the Battle of Moscow, England, the USA and 26 other countries announced the creation of an anti-German coalition.

670 out of 872 days of the siege, Govorov led the heroic defense of Leningrad

After the Battle of Moscow, on the recommendation of G.K. Zhukova L.A. Govorov in April 1942 was sent to Leningrad as the commander of a group of troops of the Leningrad Front, which directly defended the city. In June of the same year, the Headquarters appointed him commander of the troops of the entire Leningrad Front.

In Leningrad, city leaders accepted this appointment without enthusiasm. They were confused by many things: he served with the whites, he was non-partisan. Moreover, he is not talkative and reserved.

But within a few months, the 1st Secretary of the Leningrad Regional Committee and City Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) A.A. Zhdanov will say among his comrades: “Perhaps, a better commander than Govorov cannot be found for the Leningrad Front.”

Just like in 1941, when L.A. Govorov took command of the combined arms army; for the first time in Soviet military history, an artillery general became a front commander. And again, as near Moscow, the situation demanded it.

And the situation in Leningrad was extremely difficult. The dilapidated city was surrounded by a blockade, in dire need of food, and at the same time suffering daily from systematic artillery shelling and air raids. “I am responsible for Leningrad, and I will not give it to the enemy,” Govorov wrote to his wife in Moscow in July 1942.

Commander of the Leningrad Front

Lieutenant General of Artillery L.A. Govorov, 1942

He constantly remembered the two main tasks assigned to him by Headquarters and personally by I.V. Stalin: the first was to protect the city from destruction by enemy artillery, the second was to accumulate forces for the upcoming attack on the enemy.

In a short time, Govorov built a long-term and stable defense system, insurmountable to the enemy. 110 large defense centers were created, many thousands of kilometers of trenches, communication passages and other engineering structures were equipped. This created the opportunity to secretly regroup troops, withdraw soldiers from the front line, and bring up reserves. Govorov checked the quality of defensive work personally and it was very “unfortunate” for those division commanders in whose sector it was impossible to walk full-length through the trenches from the command post to the front line. As a result of these measures, the number of losses of our troops from shell fragments and enemy snipers has sharply decreased.

Govorov sought not only to hold Leningrad, but to conduct an active defense, undertaking reconnaissance, private offensive actions, and delivering powerful fire strikes against enemy groups. As Govorov later recalled, the idea of attacking from a besieged city gave birth to a powerful offensive impulse and gave the Soviet troops a powerful factor - operational surprise.

Those who served and worked with L.A. at this time. Govorov, noted that his distinguishing features as a commander were enormous self-control, calmness and composure in the most difficult and tense situations. He introduced planning, systematicity and high organization into the management of front troops.

For over two years, in the conditions of a besieged city, the front artillerymen waged a counter-battery fight against the enemy’s siege artillery. To increase the firing range of the guns, Govorov took unconventional measures: he moved forward the positions of heavy artillery, secretly transferred some of it across the Gulf of Finland to the Oranienbaum bridgehead, which made it possible to increase the firing range, both to the flank and rear of enemy artillery groups. For these purposes, the naval artillery of the Baltic Fleet was also used.

The damage caused to Leningrad decreased, not only due to a decrease in the intensity of shelling due to the destroyed guns, but also because the enemy was forced to spend most of the shells on fighting Soviet artillery. By 1943, the number of enemy shells falling on the city had decreased 7 times! As a result, many thousands of human lives and enormous material and cultural values, including outstanding historical and architectural monuments, were saved.

With the direct participation of L.A. Govorov, the number of people transported from besieged Leningrad along the Road of Life and the amount of products imported into the city doubled, both due to the strengthening of artillery and air cover of the ice road, and thanks to his order to allocate all free military vehicles for these goals.

- a set of defensive and offensive operations of Soviet troops in the Great Patriotic War, carried out from September 30, 1941 to April 20, 1942 in the western strategic direction with the aim of defending Moscow and the Central Industrial Region, defeating the strike groups of German troops that threatened them. It included the strategic Moscow defensive operation (September 30 - December 5, 1941), the Moscow offensive operation (December 5, 1941 - January 7, 1942), the Rzhev-Vyazma operation (January 8 - April 20, 1942) and the frontal Toropetsko-Kholm operation (January 9 - February 6, 1942). The Battle of Moscow involved troops of the Kalinin, Western, Reserve, Bryansk, left wing of the North-Western and right wing of the South-Western fronts, troops of the country's Air Defense, and Air Force. They were opposed by the German Army Group Center.

By the beginning of the Battle of Moscow, the situation for the Soviet troops was extremely difficult. The enemy deeply invaded the country, capturing the Baltic states, Belarus, Moldova, a significant part of Ukraine, blockaded Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and reached the distant approaches to Moscow. After the failure of the plan to capture Moscow on the move in the first weeks of the war, the Nazi command prepared a major offensive operation codenamed Typhoon. The operation plan provided for dismembering the defenses of the Soviet troops with three powerful strikes of tank groups from the areas of Dukhovshchina, Roslavl and Shostka in the eastern and north-eastern directions, encircling and destroying Soviet troops in the areas west of Vyazma and east of Bryansk. Then, with strong mobile groups, it was planned to cover Moscow from the north and south and, in cooperation with the troops advancing from the front, take possession of it.

The German Army Group Center, intended for the offensive, had 1.8 million people, over 14 thousand guns and mortars, 1.7 thousand tanks and 1390 aircraft. Soviet troops numbered 1.25 million people, 7.6 thousand guns and mortars, 990 tanks, 677 aircraft (including reserve air groups).

The Nazi troops began the offensive according to the Typhoon plan on September 30, 1941 in the Bryansk and October 2 in the Vyazma directions. Despite the stubborn resistance of the Soviet troops, the enemy broke through their defenses. On October 6, he entered the area west of Vyazma and encircled there the four armies of the Western and Reserve (10 October merged with the Western) fronts. By their actions in encirclement, these armies pinned down 28 enemy divisions; 14 of them could not continue the offensive until mid-October.

A difficult situation also developed in the Bryansk Front. On October 3, the enemy captured Oryol, and on October 6, Bryansk. On October 7, the front troops were surrounded. Breaking out of encirclement, the armies of the Bryansk Front were forced to retreat. By the end of October, Nazi troops reached the approaches to Tula.

In the Kalinin direction, the enemy launched an offensive on October 10 and captured the city of Kalinin (now Tver) on October 17. In the second half of October, the troops of the Kalinin Front (created on October 17) stopped the advance of the enemy's 9th Army, taking an enveloping position in relation to the left wing of Army Group Center.

By the beginning of November, the front passed along the line of Selizharovo, Kalinin, the Volga Reservoir, along the rivers Ozerna, Nara, Oka and further Tula, Novosil. In mid-November, fighting began on the near approaches to Moscow. They were especially persistent in the Volokolamsk-Istra direction. On November 23, Soviet troops left Klin. The enemy captured Solnechnogorsk, Yakhroma, and Krasnaya Polyana. At the end of November - beginning of December, German troops reached the Moscow-Volga canal, crossed the Nara River north and south of Naro-Fominsk, approached Kashira from the south, and captured Tula from the east. But they didn't go any further. On November 27, in the area of Kashira and on November 29, north of the capital, Soviet troops launched counterattacks on the southern and northern enemy groups, and on December 3-5 - counterattacks in the areas of Yakhroma, Krasnaya Polyana and Kryukov.

By staunch and active defense, the Red Army forced the fascist strike groups to disperse over a huge front, which led to the loss of offensive and maneuver capabilities. Conditions were created for the Soviet troops to launch a counteroffensive. Reserve armies began to move into the zones of the upcoming actions of the Red Army. The idea of the counter-offensive of the Soviet troops was to simultaneously defeat the most dangerous enemy strike forces that threatened Moscow from the north and south. The troops of the Western, Kalinin and right wing of the Southwestern (December 18, 1941 transformed into the Bryansk Front) fronts were involved in the Moscow offensive operation.

The counteroffensive began on December 5 with a strike from the left wing of the Kalinin Front. Conducting intense battles, by January 7, Soviet troops reached the Volga River northwest and east of Rzhev. They advanced 60-120 kilometers in the southern and southwestern directions, taking up an enveloping position in relation to the German troops located in front of the Western Front.

The armies of the right wing of the Western Front, which launched a counteroffensive on December 6, liberated Istra, Klin, Volokolamsk and threw the enemy 90-110 kilometers westward, eliminating the threat of bypassing Moscow from the north. The armies of the left wing of the Western Front launched powerful blows from several directions against the enemy’s 2nd Tank Army, which was deeply wedged into the defenses. The fascist German command, fearing the encirclement of its troops east of Tula, began to withdraw them to the west. By the end of December 16, the immediate threat to Moscow was eliminated from the south.

During the offensive, the right-flank armies of the Southwestern Front liberated up to 400 settlements and liquidated the Yelets ledge on December 17.

Continuing the offensive, by the beginning of January 1942, Soviet troops pushed the enemy back 100-250 kilometers, inflicted heavy damage on 38 divisions, and liberated over 11 thousand settlements.

At the beginning of January 1942, the Headquarters of the Supreme High Command decided to launch a general offensive by Soviet troops near Leningrad, as well as in the western and southwestern directions. The troops of the western direction were tasked with encircling and defeating the main forces of Army Group Center.

The offensive, which unfolded over a vast area, was carried out in separate directions, and the fronts began operations at different times and under different conditions. In the western direction, the troops of the Western and Kalinin fronts carried out the Rzhev-Vyazemskaya operation, and the left wing of the North-Western (from January 22 of the Kalinin) front - the Toropetsko-Kholm operation, as a result of which the Germans were thrown back another 80-250 kilometers from the capital. Soviet troops penetrated deeply into their defenses at the junction of Army Groups North and Center, disrupting operational cooperation between them. However, it was not possible to encircle and destroy the main forces of Army Group Center.

Despite the incompleteness, the general offensive in the western direction achieved significant success. The enemy was thrown back 150-400 kilometers to the west, the Moscow and Tula regions, and many areas of the Kalinin and Smolensk regions were liberated.

The enemy lost more than 500 thousand people, 1.3 thousand tanks, 2.5 thousand guns and other equipment killed, wounded and missing.

Germany suffered its first major defeat in World War II.

In the Battle of Moscow, Soviet troops also suffered significant losses. Irreversible losses amounted to 936,644 people, sanitary losses - 898,689 people.

The outcome of the Battle of Moscow had enormous political and strategic consequences. A psychological turning point occurred among soldiers and civilians: faith in victory strengthened, the myth of the invincibility of the German army was destroyed. The collapse of the plan for a lightning war (Barbarossa) raised doubts about the successful outcome of the war among both the German military-political leadership and ordinary Germans.

The Battle of Moscow was of great international importance: it helped strengthen the anti-Hitler coalition and forced the governments of Japan and Turkey to refrain from entering the war on the side of Germany.

For the exemplary performance of combat missions during the Battle of Moscow and the valor and courage displayed at the same time, about 40 units and formations received the title of Guards, 36 thousand Soviet soldiers were awarded orders and medals, of which 110 people were awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. In 1944, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR established the medal "For the Defense of Moscow", which was awarded to more than one million defenders of the city.

(Additional

Due to the critical situation on the outskirts of the capital, on October 20 Moscow was declared in a state of siege. The defense of the lines 100-120 kilometers away was entrusted to the commander of the Western Front, Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov, and at its closest approaches - to the head of the Moscow garrison P.A. Artemyev.

Due to the critical situation on the outskirts of the capital, on October 20 Moscow was declared in a state of siege. The defense of the lines 100-120 kilometers away was entrusted to the commander of the Western Front, Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov, and at its closest approaches - to the head of the Moscow garrison P.A. Artemyev. The need to strengthen the rear and to intensify the fight against the subversive actions of enemy agents was pointed out.

The population of Moscow was actively involved in the construction of defensive structures around the capital and inside the city. In the shortest possible time, the city was surrounded by anti-tank ditches, hedgehogs, and forest rubble. Anti-tank guns were installed in tank-dangerous areas. From Muscovites, militia divisions, tank destroyer battalions, and combat squads were formed, which, together with regular army units, participated in battles and in maintaining order in the city.

Enemy air raids on Moscow were successfully repelled. By the beginning of the Battle of Moscow, the capital's air defense had a coherent system based on the principle of all-round defense, taking into account the most dangerous directions - the western and southwestern, as well as on the maximum use of the combat capabilities of fighter aircraft and anti-aircraft weapons, which closely interacted with each other.

Fighter aircraft fought against enemy air at distant approaches. Its airfields were located within a radius of 150-200 kilometers from Moscow, but as the Germans approached the capital, they relocated closer and closer. During the daytime, fighters operated throughout the entire depth of the defense, and at night, within the light searchlight fields.

On the immediate approaches to Moscow, German planes were fired upon and destroyed by predominantly medium-caliber anti-aircraft artillery. Its fire was controlled in sectors, each of which housed one anti-aircraft artillery regiment. The regiments formed battle formations in three lines, which had considerable depth. Units and subunits of small-caliber anti-aircraft artillery and anti-aircraft machine guns were used to provide air cover for important objects inside the city (the Kremlin, train stations, power plants).

Retreating, the German bombers dropped their deadly cargo anywhere.

In October, the enemy carried out 31 raids on Moscow, involving 2018 aircraft, of which 278 were shot down. Moscow's air defense troops fought an intense battle with the air enemy and defended the capital from destruction.

The control of Moscow air defense forces and means was carried out centrally from the command post of the 1st Air Defense Corps. The commander of the Moscow air defense zone was General M. S. Gromadin.

In October, fascist aviation carried out 31 raids on Moscow. About 2 thousand aircraft took part in them, but only 72 were able to break through to the bombing targets 1. While repelling the raids in air battles and anti-aircraft artillery fire, 278 German aircraft 2 were shot down.

In the second half of October, it was possible to delay the advance of fascist German troops in the Bryansk Front. This allowed the 3rd and 13th armies, which had been engaged in heavy fighting behind enemy lines for almost three weeks, to break out of encirclement on October 23 and, by order of Headquarters, retreat to a line east of Dubna, Plavsk, Verkhovye, Livny.

The actions of the front troops pinned down the 2nd Tank Army in the Tula direction. She was able to resume attacks only at the end of October, when the offensive of the 4th Army of Army Group Center had already stalled. The enemy's tank divisions advanced from Mtsensk to Tula by October 29, but were stopped here. “The attempt to capture the city on the move,” Guderian wrote after the war, “ran up against strong anti-tank and air defense and ended in failure, and we suffered significant losses in tanks and officers.” For three days, the Nazis furiously attacked Tula, but the troops of the 50th Army and the Tula combat sector, together with the militia, defended themselves selflessly. Communists and Komsomol members of the city and region joined the ranks of the defenders. Their courage was amazing. The Tula people turned their city into an impregnable fortress and did not surrender it to the enemy. A major role in organizing the struggle for Tula was played by the city defense committee, headed by the first secretary of the regional party committee V.G. Zhavoronkov, who in those days was a member of the Military Council of the 50th Army.

The defense of Tula ensured the stability of the left wing of the Western Front on the far southern approaches to the capital. It also contributed to stabilizing the situation on the Bryansk Front.

Thus, the October offensive of fascist German troops on Moscow failed. The enemy was forced to go on the defensive on the line Selizharovo, Kalinin, Tula, Novosil.

The most important condition for thwarting the enemy's intentions was the creation of reserves in a short time, most of which were brought into battle in the Western Front at the turn of the Mozhaisk defense line.

Along with the ground forces, the Soviet Air Force played a huge role in repelling the fierce onslaught of the Nazis. In the first nine days of the enemy offensive on Moscow alone, Western Front aviation, the 6th Air Defense Aviation Corps and DVA units carried out 3,500 sorties, destroying a significant number of enemy aircraft, tanks and manpower. In total, from September 30 to October 31, the Air Force carried out 26 thousand sorties, of which up to 80 percent were to support and cover troops.

The enemy also experienced the force of powerful attacks from Soviet tanks and artillery. Tank brigades blocked the path of fascist troops in particularly dangerous directions.

To disrupt the enemy's offensive, anti-tank areas and strongholds, as well as various engineering obstacles, were set up.

Soldiers of all branches of the military in the battles on the outskirts of Moscow showed examples of fulfilling military duty and the irresistible strength of moral spirit, and showed mass heroism. In these battles, units of the rifle divisions distinguished themselves: the 316th under General I.V. Panfilov, the 78th under Colonel A.P. Beloborodov, the 32nd under Colonel V.I. Polosukhin, the 50th under General N.F. Lebedenko, the 53rd 1st Colonel A.F. Naumov, 239th Colonel G.O. Martirosyan, as well as the 1st Guards Motorized Rifle Division Colonel A.I. Lizyukov, the cavalry group of General L.M. Dovator, tank brigades led by M.E. Katukov, P. A. Rotmistrov, I. F. Kirichenko, M. T. Sakhno, and many other compounds.

The results of the October offensive did not please the Nazis. The main goals of Operation Typhoon - the destruction of the Soviet Army and the capture of Moscow - were not achieved. The outcome of the bloody battles was unexpected not only for the soldiers, but also for the Wehrmacht generals.

The stubborn resistance of the Soviet troops was the main reason for the hesitation that appeared among the Wehrmacht command, the divergence of opinions in determining the ways of further waging the war against the Soviet Union. At the beginning of November, Franz Halder, at that time the chief of the German General Staff, wrote in his diary: “We must, by analyzing the current situation, accurately determine our capabilities for conducting subsequent operations. There are two extreme points of view on this issue: some consider it necessary to gain a foothold on the achieved positions, others demand to actively continue the offensive.”

But in fact, the Nazis had no choice. Winter was approaching, and the goals of Plan Barbarossa remained unfulfilled. The enemy was in a hurry, trying at all costs to capture the capital of the Soviet Union before the onset of winter.

The plan of the fascist German command to continue the offensive in November contained the same idea as in October: with two mobile groups, simultaneously deliver crushing blows to the flanks of the Western Front and, quickly bypassing Moscow from the north and south, close the encirclement ring east of the capital.

In the first half of November, the fascist German command regrouped its troops: from near Kalinin it transferred the 3rd Tank Group to the Volokolamsk-Klin direction, and replenished the 2nd Tank Army with more than a hundred tanks, concentrating its main forces on the right flank to bypass Tula .

Army Group Center by November 15, 1941 included three field armies, one tank army and two tank groups, numbering 73 divisions (47 infantry, 1 cavalry, 14 tank, 8 motorized, 3 security) and 4 brigades.

The task of enveloping Moscow from the north (Operation Volga Reservoir) was assigned to the 3rd and 4th German tank groups consisting of seven tank, three motorized and four infantry divisions, and from the south to the 2nd Panzer Army consisting of four tank, three motorized and five infantry divisions. The 4th Army was to conduct a frontal offensive, pin down the main forces of the Western Front, and then destroy them west of Moscow. The 9th and 2nd armies, shackled by the troops of the Kalinin and Southwestern fronts, were actually deprived of the opportunity to take part in the November offensive. In total, the fascist German command allocated 51 divisions, including 13 tank and 7 motorized, directly for the capture of Moscow.

Assessing the current situation, the Soviet command clearly understood that the relative weakening of tension on the front near Moscow was temporary, that although the enemy had suffered serious losses, it had not yet lost its offensive capabilities, retained the initiative and superiority in forces and means, and would persistently strive to capture Moscow. Therefore, all measures were taken to repel the expected attack. At the same time, new armies were formed and deployed at the line of Vytegra, Rybinsk, Gorky, Saratov, Stalingrad, Astrakhan as strategic reserves.

The headquarters, having determined the enemy’s intentions and capabilities, decided

strengthen the most dangerous areas first. She demanded

from the Western Front, in cooperation with the troops of the Kalinin and right wing of the Southwestern Front, to prevent a bypass of Moscow from the north

west and south. His armies were reinforced with anti-tank artillery and

guards mortar units. In Volokolamsk and Serpukhov

in these directions the reserves of the Headquarters were concentrated; The 16th Army was re-

three cavalry divisions were given; the 2nd Cavalry Corps (two divisions) arrived in the Podolsk, Mikhnevo area from the Southwestern Front, part

which additionally included rifle and tank divisions. For the first

half of November the Western Front received a total of 100 thousand.

Kalinin Front - 30th Army.

The German shock groups were opposed by the 30th, 16th and partly the 5th armies on the right and the 50th and 49th armies on the left wing of the Western Front.

The command of the Western Front, having strengthened the troops operating north-west and south-west of Moscow, organized counterattacks in the 16th Army zone towards Volokolamsk and in the Skirmanovo area, as well as in the 49th Army zone - in the Serpukhov direction. According to the fascist command, the counterattack in the 49th Army zone did not allow the 4th German Army to go on the offensive here in the second half of November 3.

In total, the troops of the Western Front (including the 30th Army) by mid-November included 35 rifle, 3 motorized rifle, 3 tank, 12 cavalry divisions, 14 tank brigades. As before, the Soviet divisions were significantly inferior in number to the German ones. Despite the strengthening of the troops of the Western Front, the fascist German armies in November continued to maintain an overall numerical superiority in men and military equipment near Moscow, especially in the directions of the main attacks. So, in the Klin direction, against 56 tanks and 210 guns and mortars that the 30th Army had, the enemy had up to 300 tanks and 910 guns and mortars.

By concentrating about 1,000 aircraft near Moscow (although many of them were of outdated types), the Soviet command created a quantitative superiority over the enemy in aviation. To gain air supremacy, the Headquarters ordered the commander of the Air Force of the Soviet Army to carry out an operation to destroy German aviation at airfields from November 5 to 8. The air forces of the Kalinin, Western, Bryansk fronts, the 81st DBA division and the aviation of the Moscow defense zone were involved in it. 28 enemy airfields were hit, and on November 12 and 15, 19 more, where 88 aircraft were destroyed.

Much attention was paid to the engineering equipment of the area. The troops improved their positions and created operational barrier zones. Intensive construction of defensive lines continued. On the outer border of the Moscow zone alone, by November 25, 1,428 bunkers, 165 km of anti-tank ditches, 110 km of three-row wire fences and other obstacles had been built.

The air defense of the capital continued to be strengthened and improved. According to the decision of the State Defense Committee of November 9, 1941, the country's air defense zones were removed from the subordination of the military councils of districts and fronts and were subordinate to the Deputy People's Commissar of Defense for Air Defense, who actually became the commander of the country's Air Defense Forces as an independent branch of the USSR Armed Forces. At the same time, all air defense zones in the European part of the Soviet Union were transformed into divisional and corps air defense areas. The Moscow air defense zone became the Moscow corps air defense region.

In those difficult days, the Soviet people celebrated the 24th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution. The ceremonial meeting of the Moscow Council of Workers' Deputies on November 6, the parade of troops on Red Square on November 7 and the speeches of the Chairman of the State Defense Committee I.V. Stalin played an important role in strengthening the confidence of the people and the army that the enemy near Moscow would be stopped, that here, at walls of the capital, the defeat of the Nazi invaders will begin.

Addressing the soldiers leaving Red Square for the front, J.V. Stalin said on behalf of the party and the people: “The whole world is looking at you as a force capable of destroying the predatory hordes of German invaders. The enslaved peoples of Europe, who fell under the yoke of the German invaders, look at you as their liberators.”

After a two-week pause, Army Group Center resumed its attack on the Soviet capital. On the morning of November 15, powerful artillery and aviation preparation began, and then the 3rd Tank Group dealt a strong blow to the 30th Army of General D. D. Lelyushenko. Part of the troops of this army, located north of the Volga Reservoir, by order of the command on November 16, retreated to the northeastern bank of the Volga.

The formations defending south of the reservoir offered stubborn resistance to the enemy. Only in the second half of November 16 was the enemy able to cross the Lama River, losing up to 60 tanks and armored vehicles. By the end of November 17, he managed to reach the Novozavidovsky area. The situation at the junction of the Kalinin and Western fronts became extremely complicated. To eliminate the threat of an enemy breakthrough to Klin, the front command reinforced the 30th Army with two divisions and organized several air strikes in its zone against the advancing enemy troops.

On November 16, in the Volokolamsk direction, the 4th German Tank Group (at least 400 tanks) with massive air support went on the offensive against the 16th Army. Its main blow fell at the junction of the 316th Infantry Division of General I.V. Panfilov and the group of troops of General L.M. Dovator. In decisive battles with the fascists, Panfilov’s heroes immortalized their names. In the area of the Dubosekovo crossing, 28 Panfilov men, having destroyed 18 tanks and dozens of fascists in four hours of unequal battle, did not let the enemy through.

And on the same day, part of the forces of the 16th Army, with the support of aviation, launched a powerful counterattack on the enemy. The defenders of Moscow also fought steadfastly on other sectors of the front. In the Istra direction, the 78th Infantry Division defended itself especially stubbornly.

Events at the front in the period from November 16 to 21 showed that the main forces of the 3rd and 4th Panzer Groups, which had the task of making quick operational breakthroughs and a rapid bypass of Moscow, found themselves drawn into protracted battles. The pace of the enemy offensive continuously decreased and did not exceed 3-5 km per day even among mobile troops. The Nazis had to overcome strong defenses, while repelling counterattacks from rifle, tank and cavalry formations. The enemy's attempts to encircle any division were, as a rule, unsuccessful. To capture each subsequent line, he was forced to organize the offensive anew.

The Western Front was actively assisted by Kalininsky, whose troops firmly pinned down the 9th German field army, not allowing it to transfer a single division to the Moscow direction.

On November 19, the command of Army Group Center, having strengthened the 3rd Tank Group with tank and motorized divisions, demanded that it capture Klin and Solnechnogorsk as soon as possible. To avoid encirclement, Soviet troops abandoned these cities on November 23 after stubborn street fighting.

The enemy's pressure did not weaken in other sectors of the defense either. Particularly stubborn battles were fought by the troops of the 16th and partly the 5th armies at the turn of the Istra River. Soviet divisions held back the fierce attacks of the Nazis here for three days and inflicted great damage on them. However, on November 27, the 16th Army had to leave the city of Istra.

Despite significant losses, the enemy continued to rush towards Moscow, using up their last reserves. But he failed to cut through the defense front of the Soviet troops.

The Soviet command assessed the created situation as very dangerous, but not at all hopeless. It saw that the troops were determined to prevent the enemy from approaching Moscow and were fighting steadfastly and selflessly. Every day it became more obvious that the enemy’s capabilities were not unlimited and as reserves were spent, his onslaught would inevitably weaken.

The assessment of the current situation given by the Wehrmacht leadership in those days can be judged by Halder’s entry in his service diary: “Field Marshal von Bock personally directs the course of the battle near Moscow from his forward command post. His... energy drives the troops forward... The troops are completely exhausted and incapable of attacking... Von Bock compares the current situation with the situation in the battle of the Marne, pointing out that a situation has arisen where the last battalion thrown into battle can decide the outcome battles." However, the Nazis’ calculations for each “last” battalion did not come true. The enemy suffered heavy losses, but was unable to break through to Moscow.

After the capture of Klin and Solnechnogorsk, the enemy made an attempt to develop his attack northwest of Moscow. On the night of November 28, he managed with a small force to cross to the eastern bank of the Moscow-Volga canal in the Yakhroma area north of Iksha.

The Headquarters of the Supreme High Command and the command of the Western Front took urgent measures to eliminate the created danger. Reserve formations and troops from neighboring areas were transferred to the Kryukovo, Khlebnikovo, and Yakhroma areas. An important role in changing the situation north of Moscow was played by the timely movement from reserve to the line of the Moscow-Volga canal between Dmitrov and Iksha of the 1st Shock Army under the command of General V.I. Kuznetsov. Its advanced units pushed the enemy back to the western bank of the canal.

At the end of November and beginning of December, the 1st Shock and the newly formed 20th Armies, with the active support of the aviation group of General I. F. Petrov, launched a series of counterattacks against the Nazi troops and, together with the 30th and 16th Armies, finally stopped them further promotion. The enemy was forced to go on the defensive. The threat of a breakthrough to Moscow from the north-west and north was eliminated.

Events on the left wing of the Western Front unfolded extremely sharply and intensely. Here the 2nd German Tank Army was able to resume the offensive only on November 18. After unsuccessful attempts to capture Tula from the south and north-west, the command of Army Group Center decided to launch an offensive in a northerly direction, bypassing the city from the east.

The strike force of the 2nd Tank Army, consisting of four tank, three motorized, and five infantry divisions, supported by aviation, broke through the defenses of the 50th Army and, developing an offensive, captured Stalinogorsk (Novomoskovsk) on November 22. Its formations rushed towards Venev and Kashira. Fierce fighting broke out.

The front commander demanded that the 50th Army “under no circumstances allow the enemy to penetrate into the Venev area.” This city and the approaches to it were defended by a combat group consisting of a regiment of the 173rd Infantry Division, the 11th and 32nd Tank Brigades (30 light tanks), and a tank destroyer battalion formed from the local population. Without breaking the group's resistance with frontal attacks, the 17th German Panzer Division bypassed the city from the east. On November 25, its advanced units found themselves 10-15 km from Kashira.

The other two divisions of the 2nd Tank Army advanced on Mikhailov and Serebryanye Prudy. The Nazis sought to take Kashira as quickly as possible and seize the crossings on the Oka.

To stop the advance of the enemy’s southern attack group, the Western Front command on November 27 carried out a counterattack in the Kashira area with formations reinforced by tanks and rocket artillery of the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps. As a result of the counterattack, the corps, with the support of front aviation and Moscow air defense units, inflicted a heavy defeat on the enemy's 17th Tank Division and by November 30th threw it back to the Mordves area.

Thus, the stubborn defense of Tula and the persistent resistance of Soviet troops in the areas of Stalinogorsk and Venev thwarted the enemy’s plans. The 2nd Tank Army was unable to capture the crossings across the Oka River.

After this failure, the Nazis made desperate attempts to capture Tula with a blow from the east and northeast. They believed that in the current situation it was impossible to “conduct further operations to the north or east... without first capturing this important communications hub and airfield.”

On December 3, the enemy managed to cut the railway and highway north of Tula. At the same time, he increased pressure on the city from the west at the junction of the 49th and 50th armies. The struggle reached its highest intensity. To eliminate the breakthrough north of Tula, the 50th Army of General I.V. Boldin launched a counterattack on the enemy in the Kostrovo, Revyakino area, where it surrounded part of the forces of the 4th German Tank Division.

Active actions by the troops of the left wing of the Western Front in early December forced the 2nd German Tank Army to begin withdrawing. At the critical moment of the battle in the Kashira and Tula regions, she could not receive help from her neighbor on the right - the 2nd Field Army, the main forces of which were drawn into protracted battles with the troops of the 3rd and 13th armies of the Southwestern Front in the Yelets direction.

The enemy suffered setbacks north and south of Moscow. On December 1, he tried to break through to the city in the center of the Western Front. He dealt strong blows in the Naro-Fominsk area and pushed back the defending divisions. The front command immediately responded to this with a counterattack, using the reserve of the 33rd and neighboring armies. The enemy was driven back across the Nara River with heavy losses. Thus, his last attempt to save Operation Typhoon failed. The Nazis also failed to carry out their plan to destroy Moscow with air strikes. Strengthening air defense has yielded results. In November, only a few planes broke through to the city. In total, during the period July - December 1941, Moscow air defense forces repelled 122 air raids, in which 7,146 aircraft took part. Only 229 aircraft, or a little more than 3 percent, were able to break through to the city.

The Nazis' attempts to carry out extensive reconnaissance, sabotage, terrorist and other subversive activities were also unsuccessful. State security agencies neutralized about 200 fascist agents in the capital and its suburbs. In addition, in the combat area of the Western Front, border guard units for rear protection detained over 75 spies and saboteurs, and eliminated several enemy sabotage and reconnaissance groups. In the Moscow direction, the enemy did not manage to commit a single sabotage in the rear of the Soviet troops, disrupt the work of industrial enterprises, transport, or disrupt the supply of the active army. Using captured and self-confessed enemy agents, Soviet counterintelligence officers, together with the military command, misinformed enemy intelligence about the location and redeployment of formations and formations of troops, their command posts, and the work of the Moscow road junction. As a result, the Nazi command did not have reliable data on the deployment of reserves to the Moscow region.

The end of November - beginning of December was a period of crisis in the Nazi offensive on Moscow. The plan to encircle and capture the Soviet capital was a complete failure. “The attack on Moscow failed. All the sacrifices and efforts of our valiant troops were in vain. We suffered a serious defeat,” Guderian wrote after the war. The enemy was completely exhausted, his reserves were exhausted. “The information we had said that all the reserves that von Bock had were used and drawn into battle,” noted Marshal of the Soviet Union K.K. Rokossovsky. The failure of Operation Typhoon became a fait accompli.

In those difficult, decisive days of the battle for the capital, Pravda wrote: “We must at all costs thwart Hitler’s predatory plan... Our whole country is waiting for this... The defeat of the enemy must begin near Moscow!”

Trains with weapons and ammunition were arriving at the front in a continuous stream. Fresh reserves of the Headquarters were concentrated in the areas northeast and southeast of the capital. Moscow and Tula became front-line arsenals of the fighting troops.

An important measure in disrupting the new enemy onslaught near Moscow was the counteroffensive organized by Headquarters in mid-November near Tikhvin and Rostov-on-Don. The Nazi Army Groups North and South, repelling the advance of Soviet troops, were deprived of the opportunity to assist Army Group Center in the decisive days. These were the first serious harbingers of great changes on the entire Soviet-German front.

So, the offensive of the Nazi troops on Moscow in November also ended in complete failure.

Army Group Center failed to achieve the objectives of Operation Typhoon. Its troops were drained of blood and lost their offensive capabilities. During the battles from November 16 to December 5, the Wehrmacht lost 155 thousand soldiers and officers, 777 tanks, hundreds of guns and mortars near Moscow. Frontline aviation and Moscow air defense forces shot down many aircraft in air battles and destroyed them at airfields. During two months of defensive battles, the Soviet Air Force carried out more than 51 thousand sorties, of which 14 percent were to provide air cover for the capital. Here, in the Moscow direction, by December 1941, they for the first time won operational supremacy in the air. The Air Guard was born in the skies of the Moscow region. The 29th, 129th, 155th, 526th Fighter, 215th Attack and 31st Bomber Aviation Regiments received the title of Guards.

On December 4-5, 1941, the defensive period of the Battle of Moscow ended. The Soviet Armed Forces defended the capital, stopping the advance of the fascist hordes.

Battle of Moscow 1941 - battles with Nazi armies that took place from October 1941 to January 1942 around the Soviet capital, which was one of the main strategic goals of the forces Axles during their invasion of the USSR. The defense of the Red Army thwarted the attack of German troops.

The German offensive, called Operation Typhoon, was planned to be carried out in two pincer encirclements: one north of Moscow against the Kalinin Front, primarily by the 3rd and 4th Panzer Groups, while simultaneously intercepting the Moscow-Leningrad railway , and the other south of the Moscow region against the Western Front south of Tula with the help of the 2nd Tank Group. The 4th German field army was supposed to attack Moscow head-on from the west.

Initially, Soviet troops conducted the defense, creating three defensive belts, deploying newly created reserve armies and transferring troops from the Siberian and Far Eastern military districts to help. After the Germans were stopped, the Red Army carried out a large counteroffensive and a series of smaller offensive operations, as a result of which the German armies were pushed back to the cities of Orel, Vyazma and Vitebsk. During this process, part of Hitler’s forces almost fell into encirclement.

Battle for Moscow. Documentary film from the series “The Unknown War”

Background to the Battle of Moscow

The original German invasion plan (Plan Barbarossa) called for the capture of Moscow four months after the start of the war. On June 22, 1941, Axis forces invaded the Soviet Union, destroyed most of the enemy air force on the ground, and advanced inland, destroying entire enemy armies through blitzkrieg tactics. The German Army Group North moved towards Leningrad. Army Group South occupied Ukraine, and Army Group Center moved towards Moscow and crossed the Dnieper by July 1941.

In August 1941, German troops captured Smolensk, an important fortress on the road to Moscow. Moscow was already in great danger, but a decisive attack on it would have weakened both German flanks. Partly out of awareness of this, partly in order to quickly seize the agricultural and mineral resources of Ukraine, Hitler first ordered the main forces to be concentrated in the northern and southern directions and to defeat the Soviet troops near Leningrad and Kiev. This delayed the German attack on Moscow. When it was resumed, the German troops were weakened, and the Soviet command was able to find new forces to defend the city.

Plan for the German attack on Moscow

Hitler believed that the capture of the Soviet capital was not a priority task. He believed that the easiest way to bring the USSR to its knees was to deprive it of its economic strength, primarily the developed regions of the Ukrainian SSR east of Kyiv. German Commander-in-Chief of the Army Walter von Brauchitsch advocated a speedy advance to Moscow, but Hitler responded by saying that “such an idea could only come to ossified brains.” Chief of the General Staff of the Ground Forces Franz Halder He was also convinced that the German army had already inflicted sufficient damage on the Soviet troops, and now the capture of Moscow would mark the final victory in the war. This point of view was shared by the majority of German commanders. But Hitler ordered his generals to first surround enemy troops around Kyiv and complete the conquest of Ukraine. This operation was successful. By September 26, the Red Army had lost up to 660 thousand soldiers in the Kyiv area, and the Germans moved on.

Advancement of German troops in the USSR, 1941

Now, from the end of the summer, Hitler redirected his attention to Moscow and entrusted this task to Army Group Center. The force that would carry out the offensive Operation Typhoon consisted of three infantry armies (2nd, 4th and 9th), supported by three tank groups (2nd, 3rd and 4th) and 2 aviation -th Air Fleet (“Luftflot 2”) Luftwaffe. In total they amounted to two million soldiers, 1,700 tanks and 14,000 guns. The German air force, however, suffered considerable damage in the summer campaign. The Luftwaffe lost 1,603 aircraft completely destroyed and 1,028 damaged. Luftfleet 2 could provide only 549 serviceable aircraft for Operation Typhoon, including 158 medium and dive bombers and 172 fighters. The attack was supposed to be carried out using standard blitzkrieg tactics: throwing tank wedges deep into the Soviet rear, surrounding the Red Army units with “pincers” and destroying them.

Wehrmacht Three Soviet fronts confronted Moscow, forming a line of defense between the cities of Vyazma and Bryansk. The troops of these fronts also suffered greatly in previous battles. Nevertheless, it was a formidable concentration of forces of 1,250,000 soldiers, 1,000 tanks and 7,600 guns. The USSR Air Force suffered horrific losses in the first months of the war (according to some sources, 7,500, and according to others, even 21,200 aircraft). But in the Soviet rear, new aircraft were quickly manufactured. By the beginning of the Battle of Moscow, the Red Army Air Force had 936 aircraft (578 of them were bombers).

According to the operation plan, German troops were supposed to break down Soviet resistance along the Vyazma-Bryansk front, rush east and encircle Moscow, bypassing it from the north and south. However, continuous fighting weakened the power of the German armies. Their logistical difficulties were also very acute. Guderian wrote that some of his destroyed tanks were not replaced with new ones, and there was not enough fuel from the very beginning of the operation. Since almost all Soviet men were at the front, women and schoolchildren went out to dig anti-tank ditches around Moscow in 1941.

Beginning of the German offensive (September 30 – October 10). Battles of Vyazma and Bryansk

The German offensive initially went according to plan. The 3rd Panzer Army penetrated the enemy's defenses in the center, encountering almost no resistance, and rushed further to encircle Vyazma together with the 4th Panzer Group. Other units were to be supported by the 2nd Panzer Group Guderian close the ring around Bryansk. The Soviet defense was not yet fully built, and the “pincers” of the 2nd and 3rd tank groups converged east of Vyazma on October 10, 1941. Four Soviet armies (19th, 20th, 24th and 32nd) found themselves in a huge ring here .

But the surrounded Soviet troops continued to fight, and the Wehrmacht had to use 28 divisions to destroy them. This constrained the forces that could have supported the attack on Moscow. The remnants of the Soviet Western and Reserve Fronts retreated to new defensive lines around Mozhaisk. Although losses were high, some of the Soviet units were able to escape the encirclement in organized groups ranging in size from platoons to rifle divisions. The resistance of those surrounded near Vyazma gave the Soviet command time to reinforce the four armies that continued to defend Moscow (5th, 16th, 43rd and 49th). Three rifle and two tank divisions were transferred to them from the Far East, and others were on their way.

In the south, near Bryansk, the actions of the Soviet troops were just as unsuccessful as at Vyazma. The 2nd German tank group made a detour around the city and, together with the advancing 2nd Infantry Army, captured Orel by October 3, and Bryansk by October 6.

Operation Typhoon - German offensive on Moscow

But the weather began to change to the disadvantage of the Germans. On October 7, the first snow fell and quickly melted, turning roads and fields into swampy bogs. The “Russian thaw” has begun. The advance of the German tank groups slowed down noticeably, which gave the Soviet troops the opportunity to retreat and regroup.

The Red Army soldiers sometimes successfully counterattacked. For example, the 4th German Tank Division near Mtsensk was ambushed by Dmitry Lelyushenko's hastily formed 1st Guards Rifle Corps, which included Mikhail Katukov's 4th Tank Brigade. Newly created Russian tanks T-34 hid in the forest while the Germans rolled past them. Soviet infantry then held back the German advance while Soviet tanks attacked them victoriously from both flanks. For the Wehrmacht, this defeat was such a shock that a special investigation was ordered. Guderian discovered to his horror that the Soviet T-34s were almost invulnerable to the guns of German tanks. As he wrote, “our Panzer IV (PzKpfw IV) tanks with their short 75 mm cannons could only blow up a T-34 by hitting their engine from behind.” Guderian noted in his memoirs that "the Russians had already learned something."

The German advance was slowed by other counterattacks. The 2nd German Infantry Army, operating north of Guderian's forces against the Bryansk Front, came under heavy pressure from the Red Army, which had air support.

According to German data, during this first period of the battle for Moscow, 673 thousand Soviet soldiers fell into two bags - near Vyazma and Bryansk. Recent studies have given smaller, but still huge numbers - 514 thousand. The number of Soviet troops defending Moscow thereby decreased by 41%. On October 9, Otto Dietrich from the German Ministry of Propaganda, quoting Hitler himself, predicted at a press conference the imminent destruction of the Russian armies. Since Hitler had not yet lied about military events, Dietrich's words convinced foreign correspondents that the Soviet resistance near Moscow was about to collapse completely. The morale of German citizens, which had fallen greatly since the start of Operation Barbarossa, rose noticeably. There were rumors that by Christmas the soldiers would return home from the Russian front and that the “living space” captured in the east would enrich all of Germany.

But the resistance of the Red Army had already slowed down the Wehrmacht's advance. When the first German detachments approached Mozhaisk on October 10, they came across a new defensive barrier there, occupied by fresh Soviet troops. On the same day, Georgy Zhukov, recalled from the Leningrad Front on October 6, led the defense of Moscow and the united Western and Reserve Fronts. Colonel General became his deputy Konev. On October 12, Zhukov ordered to concentrate all available forces on strengthening the Mozhaisk line. This decision was supported by the actual head of the Soviet General Staff Alexander Vasilevsky. The Luftwaffe still controlled the skies wherever they went. Stuka (Junkers Ju 87) and bomber groups flew 537 sorties, destroying approximately 440 vehicles and 150 pieces of artillery.

On October 15, Stalin ordered the evacuation of the leadership of the Communist Party, the General Staff and administrative institutions from Moscow to Kuibyshev (Samara), leaving only a small number of officials in the capital. This evacuation caused panic among Muscovites. On October 16-17, most of the capital's population tried to flee, crowding trains and clogging roads out of the city. To ease the panic somewhat, it was announced that Stalin himself would remain in Moscow.

Fighting on the Mozhaisk defense line (October 13 – 30)

By October 13, 1941, the main forces of the Wehrmacht reached the Mozhaisk defense line - a hastily built double row of fortifications on the western approaches to Moscow, which went from Kalinin (Tver) towards Volokolamsk and Kaluga. Despite recent reinforcements, only about 90,000 Soviet troops defended this line - too few to stop the German advance. Given this weakness, Zhukov decided to concentrate his forces at four critical points: General's 16th Army Rokossovsky defended Volokolamsk. Mozhaisk was defended by the 5th Army of General Govorov. The 43rd army of General Golubev was stationed at Maloyaroslavets, and the 49th army of General Zakharkin was at Kaluga. The entire Soviet Western Front - almost destroyed after the encirclement at Vyazma - was recreated almost from scratch.

Moscow itself was hastily strengthened. According to Zhukov, 250 thousand women and teenagers built trenches and anti-tank ditches around the capital, shoveling three million cubic meters of earth without the help of machinery. Moscow factories were hastily transferred to a war footing: an automobile plant began making machine guns, a watch factory produced detonators for mines, a chocolate factory produced food for the front, automobile repair stations repaired damaged tanks and military equipment. Moscow had already been subjected to German air raids, but the damage from them was relatively small thanks to powerful air defense and the skillful actions of civilian fire brigades.

On October 13, 1941, the Wehrmacht resumed its offensive. Initially, German troops attempted to bypass the Soviet defenses by moving northeast toward weakly defended Kalinin and south toward Kaluga. By October 14, Kalinin and Kaluga were captured. Inspired by these first successes, the Germans launched a frontal attack against the enemy fortified line, taking Mozhaisk and Maloyaroslavets on October 18, Naro-Fominsk on October 21, and Volokolamsk on October 27, after stubborn fighting. Due to the growing danger of flank attacks, Zhukov was forced to retreat east of the Nara River.

In the south, Guderian's Second Panzer Group initially advanced to Tula easily, because the Mozhaisk defense line did not extend that far to the south and there were few Soviet troops in the area. However, bad weather, fuel problems, destroyed roads and bridges delayed the German movement, and Guderian reached the outskirts of Tula only on October 26. The German plan envisaged a quick capture of Tula in order to extend its claw east of Moscow. However, the first attack on Tula was repulsed on October 29 by the 50th Army and civilian volunteers after a desperate battle near the city itself. On October 31, the German High Command ordered a halt to all offensive operations until the painful logistical problems were resolved and the muddy roads stopped.

Break in fighting (November 1-15)

By the end of October 1941, German troops were severely exhausted. They had only a third of their means of transportation, and their infantry divisions had been reduced to half, or even a third, of their strength. Extended supply lines prevented the delivery of warm clothing and other winter equipment to the front. Even Hitler seemed to have come to terms with the inevitability of a long struggle for Moscow, since the prospect of sending tanks into such a large city without the support of heavily armed infantry looked risky after the costly capture of Warsaw in 1939.

To boost the spirit of the Red Army and the civilian population, Stalin ordered the traditional military parade on the Red Square. Soviet troops marched past the Kremlin, heading from there straight to the front. The parade had great symbolic significance, demonstrating continued determination to fight the enemy. But despite this bright “show,” the position of the Red Army remained unstable. Although 100,000 new soldiers strengthened the defenses of Klin and Tula, where renewed German attacks were about to be expected, the Soviet line of defense remained comparatively weak. However, Stalin ordered several counter-offensives against German forces. They were started despite the protests of Zhukov, who pointed out the complete lack of reserves. The Wehrmacht repelled most of these counter-offensives, and they only weakened the Soviet forces. The Red Army's only notable success was southwest of Moscow, at Aleksin, where Soviet tanks inflicted serious damage on the 4th Army because the Germans still lacked anti-tank guns capable of fighting the new, heavily armored T-34 tanks. .

From October 31 to November 15, the Wehrmacht High Command prepared the second stage of the attack on Moscow. The combat capabilities of Army Group Center fell greatly due to battle fatigue. The Germans were aware of the continuous influx of Soviet reinforcements from the east and the presence of considerable reserves among the enemy. But given the enormity of the victims suffered by the Red Army, they did not expect that the USSR would be able to organize a strong defense. Compared to October, Soviet rifle divisions took up a much stronger defensive position: a triple defensive ring around Moscow and the remnants of the Mozhaisk line near Klin. Most Soviet troops now had multi-layered defense, with a second echelon behind them. Artillery and sapper teams were concentrated along the main roads. Finally, the Soviet troops - especially the officers - were now much more experienced.

By November 15, 1941, the ground was completely frozen and there was no more mud. The armored wedges of the Wehrmacht, numbering 51 divisions, were now going to move forward to encircle Moscow and connect to the east of it, in the Noginsk region. The German 3rd and 4th Panzer Groups had to concentrate between the Volga Reservoir and Mozhaisk, and then move past the Soviet 30th Army to Klin and Solnechnogorsk, encircling the capital from the north. In the south, the 2nd Tank Group intended to bypass Tula, still held by the Red Army, to move to Kashira and Kolomna, and from them - towards the northern claw, to Noginsk. The German 4th Infantry Army in the center was supposed to pin down the troops of the Western Front.

Resumption of the German offensive (November 15–December 4)

On November 15, 1941, the German tank armies began an offensive towards Klin, where there were no Soviet reserves due to Stalin's order to attempt a counteroffensive at Volokolamsk. This order forced the withdrawal of all forces from Klin to the south. The first German attacks split the Soviet front in two, separating the 16th Army from the 30th Army. Several days of fierce fighting followed. Zhukov recalled in his memoirs that the enemy, despite the losses, attacked head-on, wanting to break through to Moscow at any cost. But the “multi-layered” defense reduced the number of Soviet casualties. The 16th Russian Army slowly retreated, constantly snapping at the German divisions that were pressing it.

The 3rd German Panzer Group captured Klin on November 24, after heavy fighting, and Solnechnogorsk on November 25. Stalin asked Zhukov whether it would be possible to defend Moscow, ordering him to “answer honestly, like a communist.” Zhukov replied that it was possible to defend, but reserves were urgently needed. By November 28, the German 7th Panzer Division had secured a bridgehead across the Moscow-Volga Canal—the last major obstacle before Moscow—and had taken up a position less than 35 km away. from the Kremlin, but a powerful counterattack by the 1st Soviet Shock Army forced the Nazis to retreat. To the northwest of Moscow, Wehrmacht forces reached Krasnaya Polyana, a little over 20 km. from the city. German officers could see some of the large buildings of the Russian capital through field binoculars. The troops of both sides were severely depleted, some regiments were left with 150-200 fighters.

On November 18, 1941, fighting resumed in the south, near Tula. The 2nd German Panzer Group tried to surround this city. And here the German troops were badly battered in previous battles - and still did not have winter clothing. As a result, their advance was only 5-10 km. in a day. German tank crews were subjected to flank attacks by the Soviet 49th and 50th armies located near Tula. Guderian, however, continued the offensive, taking Stalinogorsk (now Novomoskovsk) on November 22, 1941 and encircling the Soviet rifle division stationed there. On November 26, German tanks approached Kashira, a city that controls the main highway to Moscow. The next day, a persistent Soviet counterattack began. General Belov's 2nd Cavalry Corps, supported by hastily put together formations (173rd Rifle Division, 9th Tank Brigade, two separate tank battalions, militia detachments), stopped the German offensive near Kashira. In early December the Germans were driven back and the southern approaches to Moscow were secured. Tula did not give up either. In the south, Wehrmacht forces did not approach Moscow as closely as in the north.

Having encountered strong resistance in the north and south, the Wehrmacht attempted on December 1 to mount a direct attack on the Russian capital from the west along the Minsk-Moscow highway, near Naro-Fominsk. But this attack had only weak tank support against powerful Soviet defenses. Faced with staunch resistance from the 1st Guards Motorized Rifle Division and flank counterattacks from the Russian 33rd Army, the German offensive stalled and was repulsed four days later by a launched Soviet counteroffensive. On December 2, one German reconnaissance battalion managed to reach the city of Khimki - about 8 km from Moscow - and capture the bridge over the Moscow-Volga canal, as well as the railway station. This episode marked the furthest breakthrough of German troops to Moscow.

Meanwhile, severe frosts began. November 30th Fedor von Bock reported to Berlin that the temperature was -45 ° C. Although, according to the Soviet weather service, the lowest temperature in December reached only -28.8 ° C, German troops without winter clothing froze even with it. Their technical equipment was not suitable for such harsh weather conditions. More than 130 thousand cases of frostbite were reported among German soldiers. The oil in the engines froze; the engines had to be warmed up for several hours before use. The cold weather also harmed the Soviet troops, but they were better prepared for it.

The Axis advance on Moscow stopped. Heinz Guderian wrote in his diary: “the attack on Moscow failed... We underestimated the enemy’s strength, distances and climate. Fortunately, I stopped my troops on December 5, otherwise disaster would have been inevitable."

Some historians believe that artificial floods played an important role in the defense of Moscow. They were organized mainly to break the ice and prevent German troops from crossing the Volga and the Moscow Sea. The first such act was the explosion of the dam of the Istra reservoir on November 24, 1941. The second was the draining of water from 6 reservoirs (Khimki, Iksha, Pyalovsk, Pestov, Pirogov, Klyazma) and the Moscow Sea in the Dubna area on November 28, 1941. Both were carried out by order Soviet General Staff 0428 dated November 17, 1941. These floods, in the midst of severe winter time, partially flooded about 30-40 villages.

Although the Wehrmacht advance was stopped, German intelligence believed that the Russians no longer had reserves left and would not be able to organize a counteroffensive. This assessment turned out to be wrong. The Soviet command transferred over 18 divisions, 1,700 tanks and more than 1,500 aircraft from Siberia and the Far East to Moscow. By early December, when the offensive proposed by Zhukov and Vasilevsky was finally approved by Stalin, the Red Army had created a reserve of 58 divisions. Even with these new reserves, the Soviet troops involved in the Moscow operation numbered only 1.1 million people, only slightly larger than the Wehrmacht. However, through skillful deployment of troops, a ratio of two to one was achieved at some critical points.

On December 5, 1941, a counteroffensive with the goal of “removing the immediate threat to Moscow” began on the Kalinin Front. The Southwestern and Western Fronts began their offensive operations a day later. After several days of little progress, Soviet troops in the north recaptured Solnechnogorsk on December 12, and Klin on December 15. In the south, Guderian's army hastily retreated to Venev and then to Sukhinichi. The threat to Thule was lifted.

Counter-offensive of the Russian army near Moscow in the winter of 1941

On December 8, Hitler signed Directive No. 9, ordering the Wehrmacht to go on the defensive along the entire front. The Germans were unable to organize strong defensive lines in the places where they were by that time, and were forced to retreat in order to consolidate their lines. Guderian wrote that on the same day a discussion took place with Hans Schmidt and Wolfram von Richthofen, and both of these commanders agreed that the Germans could not hold the current front line. On December 14, Halder and Kluge, without Hitler's approval, gave permission for a limited withdrawal west of the Oka River. On December 20, during a meeting with German commanders, Hitler prohibited this withdrawal and ordered his soldiers to defend every piece of land. Guderian protested, pointing out that losses from the cold exceeded combat losses and that the supply of winter equipment was hampered by the difficulties of the route through Poland. Nevertheless, Hitler insisted on defending the existing front line. Guderian was dismissed on December 25, along with Generals Hoepner and Strauss, commanders of the 4th Panzer and 9th Field Army. Feodor von Bock was also dismissed, formally for medical reasons. The commander-in-chief of the ground forces, Walter von Brauchitsch, was removed from his post even earlier, on December 19.

Meanwhile, the Soviet offensive continued in the north. The Red Army liberated Kalinin. Retreating from the Kalinin Front, the Germans found themselves in a “bulge” around Klin. The front commander, General Konev, tried to envelop the enemy troops in it. Zhukov transferred additional forces to the southern end of the “bulge” so that Konev could trap the German 3rd Tank Army, but the Germans managed to withdraw in time. Although it was not possible to create an encirclement, the Nazi defenses here were destroyed. A second encirclement attempt was made against the 2nd Tank Army near Tula, but met strong resistance at Rzhev and was abandoned. The prominence of the front line at Rzhev lasted until 1943. In the south, an important success was the encirclement and destruction of the 39th German Corps, which defended the southern flank of the 2nd Tank Army.

The Luftwaffe found itself paralyzed in the second half of December. Until January 1942, the weather remained very cold, making it difficult to start car engines. The Germans did not have enough ammunition. The Luftwaffe practically disappeared from the skies over Moscow, and the Soviet Air Force, operating from better prepared bases and supplied from close behind, strengthened. On January 4 the sky cleared. The Luftwaffe was quickly receiving reinforcements, and Hitler hoped that they would “save” the situation. Two groups of bombers arrived from Germany re-equipped (II./KG 4 and II./KG 30). Four groups of transport aircraft (102 Junkers Ju 52) were transferred to Moscow from the 4th German Air Fleet to evacuate encircled units and improve supplies for the German front. This last desperate effort by the Germans did not remain in vain. Air support helped prevent the complete defeat of Army Group Center, which the Russians were already aiming for. From December 17 to 22, Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed 299 vehicles and 23 tanks near Tula, making it difficult to pursue the retreating German army.

In the central part of the front, the Soviet advance was much slower. Only on December 26, Soviet troops liberated Naro-Fominsk, on December 28 - Kaluga, and on January 2 - Maloyaroslavets, after 10 days of fighting. Soviet reserves were running low, and on January 7, 1942, Zhukov's counteroffensive was stopped. It threw the exhausted and freezing Nazis back 100-250 km. from Moscow. Stalin demanded new offensives to trap and destroy Army Group Center, but the Red Army was overworked and these attempts failed.