Remember what kind of people are called artisans (see § 5, paragraph 1). What were they doing?

Numerous scribes served the pharaoh and the nobles. The power of the pharaoh was ensured by a large, well-trained army.

Farmers and artisans, who made up the majority of the Egyptian people, worked in the fields, in construction, and in workshops. They had to feed not only themselves, but also the pharaoh, his nobles, scribes, and warriors. Farmers paid taxes - they gave a significant part of the crop and livestock offspring to the treasury.

2. The labor of farmers. Irrigation of the fields required enormous labor. The Egyptians built on the banks of the Nile earthen embankments, separating one field from another. Thanks to the embankments, the whole country (if you imagine that you are looking from above) looked like a chessboard. During the spill, water stagnated for a long time in the squares formed by the embankments. Moisture soaked the ground, and fertile silt settled. The land became ready for plowing. For irrigating fields,

Egyptian songs of praise to the Nile and the sun

Glory to you, Nile, coming,

to revive Egypt!

Irrigating the earth

lord of fish and birds, creator of grain

and grass for livestock.

If he hesitates, life freezes

and people die.

When he comes, the earth

all living things rejoice and are in joy.

Food appears after it is spilled.

Everyone lives thanks to him

and wealth is acquired by his will.

When you set in the west, the earth plunges into darkness, like death. In the darkness, predators emerge from their lairs and poisonous reptiles crawl out. When you rise in the east, the whole earth triumphs.

From your rays the plants in the fields come to life. Birds fly from their nests and sing your praise. Your radiance penetrates the depths of the waters, and fish splash on the surface of the river. People wake up and raise their hands to you.

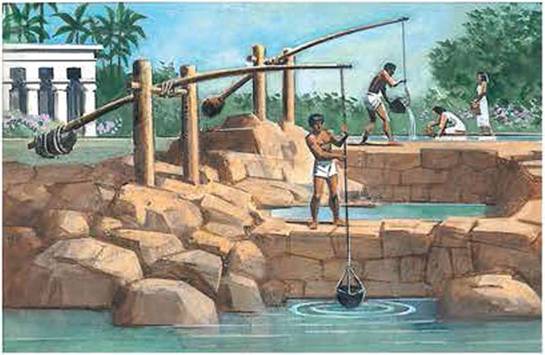

remote from the Nile, they dug canals. With the help of shadufs (see picture on p. 40) they watered gardens and vegetable gardens where water did not reach during floods.

Ancient Egyptian masters painted scenes showing the work of farmers (see figure below). In one of these images we see people loosening the ground with a plow, throwing grains of barley or wheat into moist, fertilized soil, and reaping ears of corn with sickles; A crocodile is basking on the shore. Another wall painting is dedicated to harvesting grapes and squeezing juice. After fermentation, the juice turns into wine.

Ancient Egyptian wall paintings. |

3. Visiting an Egyptian. Women will prepare flour from the grown grain by grinding it between two stones. The flour will be kneaded into dough and cakes will be baked in the hot ashes. There is little wood in Egypt, so children are sent to collect dry grass, twigs and manure, which is dried and also used as fuel for the fireplace. For lunch, in addition to flatbread, there may be one or two onions, fish dried in the wind and sun, and sometimes sweet fruits - dates, figs, grapes. On holidays, Egyptians eat meat and drink beer and grape wine.

|

|

feet), which, according to the Egyptians, protect against evil spirits and misfortunes.

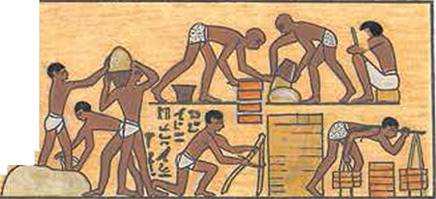

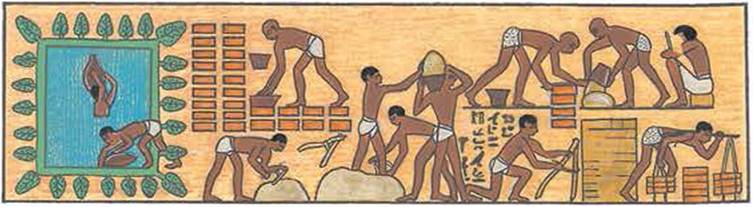

4. Crafts and exchange. An Egyptian artist who lived four thousand years ago depicted the construction of a house. One person digs up clay with a hoe, a second uses a jug to draw water from a pond, a third kneads the clay; the rest make bricks, carry them on a beam, lay out the wall and make sure it stands level.

In Egypt there were potters, weavers, tanners, carpenters, shipbuilders - it’s hard to even list all the craftsmen.

The following image has also been preserved: a woman is sitting with clay vessels in front of her. An Egyptian stands nearby, holding out a fish to her. He suggests changing - this is the simplest type of trading. There was no money then, and if they had to evaluate a product, they said: it costs the same as a cow, or as much as two bags of grain, or as much as ten copper rings.

5. Scribes collect taxes. Scribes can also be seen in ancient Egyptian images. They hold notes on their knees. IN right hand they have a reed for writing, and spare reeds behind the ear. Scribes are very necessary for nobles and

|

to the pharaoh. They will count and write down everything they are told to do: how much grain is harvested, what is the size of the fields cultivated by the farmers, and what tax each of them is obliged to pay annually.

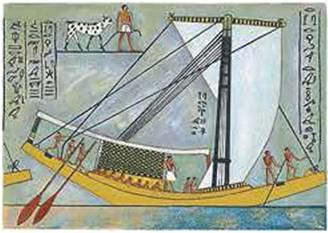

And the farmers are afraid of the scribes and complain about fate: locusts and caterpillars have ruined the Ship on the Nile. Ancient Egypt - crops, some kind of painting appeared in the fields. mice. But in due time

A boat is mooring to the shore. A scribe and several guards with rods and sticks sit in it - woe to anyone who does not have enough grain to pay the tax!

Explain the meaning of the words: nobleman, scribe, tax, irrigation, shaduf, painting, amulet.

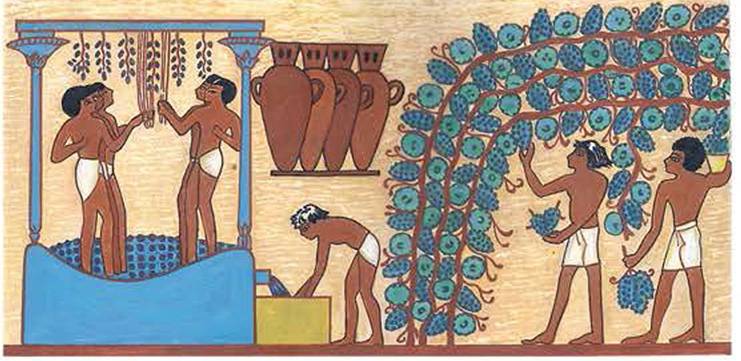

I Describe: 1. Shaduf drawing (see p. 40). Start like this: “The shaduf consists of pillars dug into the ground, a crossbar between them and a pole swinging on it. At one end of the pole there is a stone, at the other there is a leather bucket...” 2. Wall painting “Squeezing juice” (see p. 39). Start like this: “The farmers climbed into a stone barrel and, holding on to the ropes, crushed the grapes with their feet...”

Write a story on behalf of the farmer about how his day went. Include in the story a description of the farmer's clothing, his home, lunch, and work in the field (for example, plowing).

Remember what kind of people are called artisans (see § 5, paragraph 1). What were they doing?

1. Residents of Egypt: from pharaoh to simple farmer. Pharaoh was the all-powerful ruler of Egypt. The nobles—the royal advisers and military leaders—subordinated to him. Numerous scribes were in the service of the pharaoh and the nobles. The power of the pharaoh was ensured by a large, well-trained army.

Farmers and artisans, who made up the majority of the Egyptian people, worked in the fields, in construction, and in workshops. They had to feed not only themselves, but also the pharaoh, his nobles, scribes, and warriors. Farmers paid taxes - they gave a significant part of the crop and livestock offspring to the treasury.

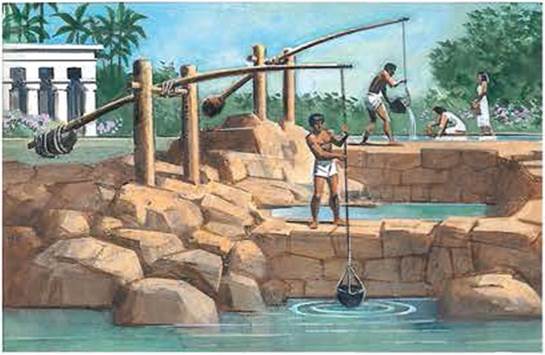

2. The labor of farmers. Irrigation of the fields required enormous labor. On the banks of the Nile, the Egyptians built earthen embankments that separated one field from another. Thanks to the embankments, the whole country (if you imagine that you are looking from above) looked like a chessboard. During the spill, water stagnated for a long time in the squares formed by the embankments. Moisture soaked the ground, and fertile silt settled. The land became ready for plowing. To irrigate fields far from the Nile, canals were dug. With the help of shadufs (see picture on p. 40) they watered gardens and vegetable gardens where water did not reach during floods.

Egyptian songs of praise to the Nile and the sun

Glory to you, Nile, coming,

to revive Egypt!

Irrigating the earth

lord of fish and birds, creator of grain

and grass for livestock.

If he hesitates, life freezes

and people die.

When he comes, the earth

all living things rejoice and are in joy.

Food appears after it is spilled.

Everyone lives thanks to him

and wealth is acquired by his will.

When you come in the west -

the earth plunges into darkness like death.

In the darkness they emerge from their lairs

predators and poisonous reptiles crawl out.

When you rise in the east -

the whole earth rejoices.

From your rays the plants in the fields come to life.

Birds fly from their nests and sing your praise.

Your radiance penetrates into the depths of the waters,

and fish splash on the surface of the river.

People wake up and raise their hands to you.

Ancient Egyptian masters painted scenes showing the work of farmers (see figure below). In one of these images we see people loosening the ground with a plow, throwing grains of barley or wheat into moist, fertilized soil, and reaping ears of corn with sickles; A crocodile is basking on the shore. Another wall painting is dedicated to harvesting grapes and squeezing juice. After fermentation, the juice turns into wine.

Ancient Egyptian wall paintings.

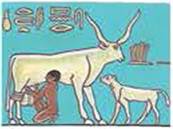

Milking. Ancient Egyptian wall painting.

Farmer's house. A drawing of our time.

3. Visiting an Egyptian. Women will prepare flour from the grown grain by grinding it between two stones. The flour will be kneaded into dough and cakes will be baked in the hot ashes. There is little wood in Egypt, so children are sent to collect dry grass, twigs and manure, which is dried and also used as fuel for the fireplace. For lunch, in addition to flatbread, there may be one or two onions, fish dried in the wind and sun, and sometimes sweet fruits - dates, figs, grapes. On holidays, Egyptians eat meat and drink beer and grape wine.

The house of a simple Egyptian is made of reeds coated with silt, with a reed mat instead of a roof. The doors here are rarely locked - there’s nothing to steal anyway. There are also mats on the earthen floor, and pottery stands near the hearth. And here are the owners - they have very little clothes on: it’s very hot. However, they love all kinds of jewelry and amulets - small objects (drilled stones, shells, beads, figurines, for example the dwarf Bes with an ugly face and crooked legs), which, according to the Egyptians, protect against evil spirits and misfortunes.

Shaduf. A drawing of our time.

Home construction. Ancient Egyptian painting.

4. Crafts and exchange. An Egyptian artist who lived four thousand years ago depicted the construction of a house. One person digs up clay with a hoe, a second uses a jug to draw water from a pond, a third kneads the clay; the rest make bricks, carry them on a beam, lay out the wall and make sure it stands level.

In Egypt there were potters, weavers, tanners, carpenters, shipbuilders - it’s hard to even list all the craftsmen.

The following image has also been preserved: a woman is sitting with clay vessels in front of her. An Egyptian stands nearby, holding out a fish to her. He suggests changing - this is the simplest type of trading. There was no money then, and if they had to evaluate a product, they said: it costs the same as a cow, or as much as two bags of grain, or as much as ten copper rings.

5. Scribes collect taxes. Scribes can also be seen in ancient Egyptian images. They hold notes on their knees. They carry a writing reed in their right hand and spare reeds behind their ears. The nobles and the pharaoh really need scribes. They will count and write down everything they are told to do: how much grain is harvested, what is the size of the fields cultivated by the farmers, and what tax each of them is obliged to pay annually.

Scribe. Ancient Egyptian image.

Barter. Ancient Egyptian image.

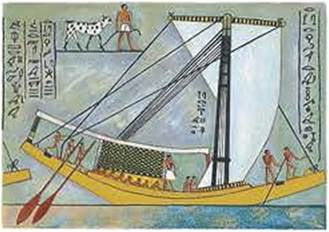

Ship on the Nile. Ancient Egyptian painting.

But the farmers are afraid of the scribes and complain about their fate: locusts and caterpillars have ruined the crops, mice have appeared in the fields. But at the appointed time, a boat moored to the shore. A scribe and several guards with rods and sticks sit in it - woe to anyone who does not have enough grain to pay the tax!

Explain the meaning of the words: nobleman, scribe, tax, irrigation, shaduf, painting, amulet.

Describe: 1. Shaduf drawing (see p. 40). Start like this: “The shaduf consists of pillars dug into the ground, a crossbar between them and a pole swinging on it. At one end of the pole there is a stone, at the other there is a leather bucket...” 2. Wall painting “Squeezing juice” (see p. 39). Start like this: “The farmers climbed into a stone barrel and... holding on to the ropes, they crush the grapes with their feet..."

Write a story on behalf of the farmer about how his day went. Include in the story a description of the farmer's clothing, his home, lunch, and work in the field (for example, plowing).

The scribe treated with contempt anyone who was engaged in physical work, but he placed the farmer below everyone else. In their work, farmers wore out as quickly as their tools. They were beaten and mercilessly exploited by their owners and tax collectors, they were robbed by their neighbors and robbed by marauders, the weather let them down, they were ravaged by locusts and rodents, all the enemies of the human race turned against them - such was the lot of the farmer. His wife could have been thrown into prison, his children could have been taken away for debts.The farmer was a complete image of an unhappy person.

However, the Greeks, who came from poor country, where the meager harvest was obtained with great difficulty, they judged the life of farmers quite differently. When the fields are sown, Herodotus said, the farmer can only calmly wait for the harvest. Diodorus, supporting his predecessor, writes:

“Usually among other peoples, agriculture requires a lot of expense and care. Only among the Egyptians it takes a little money and labor.” In addition, among the Egyptians who attended schools, there were supporters of a return to the land. These were madmen for whom the scribe painted such a gloomy picture. However, the peasant from the Salt Oasis (modern Wadi en-Natrun) appears to us not so unhappy. The land provides him with many excellent products; he loads them on his donkeys, intending to sell the harvest in Neninesut (the capital of the 20th Upper Egyptian nome, which the Greeks called Great Heracleopolis), and with the proceeds buy beautiful pies for his wife and children. As expected, evil person, seeing a small caravan, seizes the donkeys with their luggage. However, high authorities intervene. If we had read the end of this story, we would probably have learned that the justice of the pharaoh protected the villager.

The eldest of the brothers, whom another fairy tale made so famous, was not at all a pitiful poor man ("The Tale of Two Brothers"). He had a house, fields, livestock, tools, and grain. His wife lived like a noble lady, staying at home while her husband and his brother worked in the fields. She could calmly attend to her toilet. She had plenty of time to clean the house, prepare dinner before her husband arrived, and when he returned, she gave him a jug and a basin for ablution.

2. Watering gardens

While describing the Egyptian's home, we noticed their love for gardens. In the city, as in the countryside, every home owner wanted to have his own garden where he would grow fruits and vegetables. Watering the gardens was especially labor-intensive. By the way, this is the only gardening job that we know anything about. The garden and vegetable garden were divided into small squares by grooves intersecting at right angles. For a long time, and even in the era of the Middle Kingdom, gardeners went to a reservoir, filled clay round jugs, a kind of watering can, with water, brought them, hanging two on a rocker, and poured them into the head ditch, from where the water spread over other grooves, irrigating the entire garden. It was tedious and hard work. The invention of shaduf probably seemed to the Egyptians a true gift from the gods.

On the shore of the reservoir, a thick pillar about two human heights was dug vertically. It could be replaced by a tree with chopped branches if it stood on suitable place. A long pole was tied to it so that it could rotate in all directions. A heavy stone was tied to the thick end of the pole. A vessel made of canvas or baked clay was suspended from the thin one on a rope five to six cubits long. The peasant pulled the rope down to fill the vessel, then up to lift it. He poured the water into the gutter and started all over again. There were four shadufs working simultaneously in Ipui's garden.

These primitive devices are quite effective, which confirms their existence to this day. However, it appears that the New Kingdom Egyptians apparently only used them for watering gardens. They are not present in any of the scenes depicting work in the fields. Concerning sakie, wheels with pots (a water-lifting machine rotated by animals), whose creaking sound today seems inseparable from the Egyptian village, is never mentioned in documents from the times of the pharaohs. And it is not even known exactly when it appeared in the Nile Valley. In the necropolis of the priests of Thoth in Hermopolis, near the tomb of Petosiris, in Antinous and in the temple of Tanis, two wells were found large diameter. The first of them was clearly intended for sakie, however, these wells could not be ancient tombs Petosiris, which most likely dates back to the reign of Ptolemy Soter.

3. Grape harvest

Each garden had at least a small vineyard near the wall of the house or along the central alley. The vines climbed along the poles and crossbars, forming a green arch, from which, in the height of summer, hung beautiful clusters of dark blue berries, so prized by the townspeople. Viticulture has always been common in the Delta, however the main objective his is not the grapes themselves, but the wine. The wines of the Bolot region have always been famous - fur- from Imet, north of Facus, the wine of Fishing Marsh - rude- from Sin, near Pelusium, and wine from Abech, which was stored in special wicker jars - all of them are mentioned in the lists of products. But long before these lists appeared, the products of Sebahorzentipet winemakers were delivered in sealed jugs to the residence of the Tin pharaohs.

Grape harvesting and juice extraction (press) (XVIII Dynasty)

The Ramesses were great lovers of wine, as they came from Avaris, located between Imet and Sin, and in every possible way contributed to the development of viticulture and wine trade. It is to the reign of Ramses II that most of the shards from wine jars found in the Ramesseum, in Cantira and in the Theban tombs date back to the reign of Ramesses II. They would allow us to draw up at least a rough map of Egyptian winemaking if historical geography the time of the pharaohs was better studied. As for Ramses III, he said this: “I created for you (the god Amon) vineyards in the Great Oasis (modern Kharga and Dakhla) and the Small Oasis (modern Bahria), which are countless, and others [vineyards] in the south in large numbers. I multiplied them in the north to the number of hundreds of thousands. I supplied them with gardeners from prisoners of war of foreign countries, they have ponds dug by me, equipped with lotuses, they abound with must and other things, like streams of water, to bring it before your face in Thebes victorious" (translation by I.P. Sologub).

We know nothing about Egyptian viticulture and winemaking, except for one episode - the grape harvest. The pickers disperse under the arches of the vines. They pick heavy clusters of blue berries with their hands, without resorting to knives, fill baskets of palm leaves with them, trying not to crush them, because the juice from such baskets can leak, carry the baskets on their heads with songs and throw the grapes into a large vat. Then they return to the vineyard. As far as I remember, animals were never used to transport grapes. Where viticulture was especially widespread, these baskets from the vineyards were transported to the winepresses on barges so as not to crush the bunches and avoid loss of precious juice.

The vats were round and low. We do not know what material they were made from; wood should be immediately excluded. The Egyptians did not know how to make barrels, much less vats, although building a vessel is ultimately much more difficult. I think these vats were made of stone. Clay, plaster, and earthenware could fail at any moment, while hard, easily polished stone, such as granite or slate, made it possible to produce absolutely waterproof vats that did not require special care. Sometimes they were placed on a foundation two or three cubits high and decorated with reliefs. On both sides of the vat, opposite each other, stood two narrow columns or two poles with forks at the ends, if the winemaker did not pretend to be elegant. They supported a crossbar from which five or six ropes hung. When the vat was filled, the winemakers climbed into it and, holding on to the ropes, perhaps because the bottom of the vat was not flat, zealously crushed the grapes with their feet. At Mer, the vizier of Pharaoh Pepi I, two musicians sit on a rug and sing to the accompaniment of wooden rattles, encouraging the winemakers and making them dance to the same rhythm. There was no reason to forget this wonderful custom, but during the New Kingdom these assistant musicians disappear. However, the pressers, dancing in the vat, could sing themselves. The juice flowed out through two or three holes into large bowls.

After squeezing out as much as they could, the crushers poured the crushed grapes into a strong bag with poles tied to it at each end. Four people took hold of these poles and began to rotate them in different sides, twisting the bag. It was not an easy task. The crushers had to hold the heavy bag suspended and at the same time rotate the poles. At the slightest mistake, the juice flowed out onto the ground, so an assistant stood between the four pressers, who held the bag in place and placed a basin under it for the juice. During the New Kingdom, a winepress was used for this operation. It consisted of two pillars firmly dug into the ground, with two holes at the same height. A bag with two loops at the ends was suspended between them. The loops were pushed into the holes and poles were inserted into them. Now all that was left was to twist them. The crushers effectively used all their strength, and not a single drop of grape juice was wasted.

The juice collected in wide-necked vessels was poured into flat-bottomed jugs and left to ferment. When fermentation was over, the wine was poured into other jugs for transportation, long, sharp-bottomed, with two ears and a narrow neck, which was sealed with plaster. They were carried on the shoulder. When the jug was too large and heavy, it was hung from a pole and carried by two people. The scribe was present at all stages of the work. He counted the palm baskets as they were brought by the grape pickers, and wrote down on the jugs the year of manufacture, the locality, the name of the winemaker, and entered everything into his lists. The owner of the vineyard was sometimes himself present during the harvest and subsequent operations. He was immediately noticed, and the workers composed songs of praise in his honor. So, at Petosiris they sang:

"Come, our lord, look at your vineyards, which your heart rejoices in when the pressers before you crush (the grapes). The grapes on the vines are abundant. There is a lot of juice in them, more than in any other year. Drink, get drunk, do everything, "Whatever you want. Everything will come to you according to the desire of your heart. The Lady Imeta has increased your vineyards because she wishes you happiness."

“The vinedressers are gathering grapes, their children are bringing their share, it is already eight o’clock in the evening, the hour that “gives up their hands.” Night is coming. The dew of heaven is abundant on our master’s grapes.

“Everything that exists is from God. Our master will drink with pleasure, thanking God for your Ka.”

"Let us pour libations to the glory of Sha (the patron of the vine), so that he may send down abundant grapes to next year".

The Egyptians, of course, were grateful for the good harvest and prudent - they took advantage of the good disposition of the deity to ask him for new favors.

Sometimes a snake with a swollen neck, ready to attack, was depicted next to the winepress. She was married solar disk between the horns, like Isis or Hathor, and nearby were her favorite thickets of papyrus. Devout people placed in front of her a table with bread, a bunch of lettuce and a bouquet of lotuses, and next to it were two bowls. This snake is none other than Renenutet, the goddess of the harvest, on whom granaries, storerooms and vineyards depended. Her main holiday celebrated at the beginning of the season "shemu", when the harvest began. The winemakers honored her in turn when they finished pressing the grapes.

4. Plowing and sowing

Cereals remained the main agricultural crop during the Ramesses era. Fields of barley and wheat stretched interspersed throughout the valley from the Delta swamps to the rapids. Egyptian peasants were primarily cultivators. While the Nile Valley was under water, during the four months of the Akhet season, they had little to do, but when the Nile returned to its banks, they hastened to use every hour while the earth was still wet and easy to cultivate. Some paintings depicting plowing show puddles in the background, meaning that the farmers did not even wait for the flood to subside completely. In such conditions, it is possible not to carry out preliminary plowing, as is done in European countries. The storyteller chose just such a moment to begin his tale of two brothers. The older brother says to the younger: “Prepare a team for us... we will plow, because the field is out of flood, it is good for plowing. And you will also come to the field, you will come with grain for sowing, because we start plowing tomorrow morning ". That's what he said.

AND younger brother did everything whatever the elder asked. And after the earth was illuminated and the next day arrived, both went to the field with grain for sowing. And their hearts rejoiced greatly and rejoiced at their labors" (translation by M.A. Korostovtsev).

As we see, in Egypt, sowers and plowmen worked simultaneously, or, rather, the sower walked in front, and the plowman followed him, because, unlike Europe, they plowed here not in order to make a furrow, but in order to cover the sown grain with earth . The sower fills a basket with two handles, one cubit deep and about the same length, with grain. From the village he carries it on his shoulder, and in the field hangs it on a rope thrown over his neck so that it is convenient for him to take out and scatter the grain.

Even during the time of the Ramesses, the plow remained as primitive as in ancient times, when it was first invented. Even in the era of the Late Kingdom, no one wanted to improve it. Such a plow was only suitable for loosening soft ground without turf and stones. Two vertical handles connected to the crossbar were fastened at the bottom with a block, to which a metal and possibly a wooden ploughshare was attached. The drawbar was tied with a rope to the same block between the bases of the handles. At the end of it there was a wooden yoke, which was placed on the neck of two animals pulling the plow. They tied him to the horns.

The Egyptians never used bulls for plowing, but only cows. This indicates that they were not required special effort. A working cow is known to produce some milk. This means that the Egyptians had enough cows for both milk production and field work. As for the bulls, they were intended for funeral processions. The bulls dragged the sarcophagus on runners. Large stone blocks were dragged in the same way. They plowed with cows because they coped with this easy work quite well. In addition, milk yields decreased only temporarily, and this did not prevent the use of cows in the fields.

There were usually two plowmen. The hardest part was for the one holding the plow handles. At first, holding one handle, he cracked the whip. When the cows moved, he bent double and leaned on the plow with all his might. His comrade, instead of leading and pulling the team, walked backwards next to it. Sometimes it was a small naked boy; a lock of hair covered his right cheek, and in his hands he carried a small basket. He is not yet able to use a whip or a stick and only guides the cows by shouting. And sometimes the plowman’s wife walked next to the cows and scattered seeds.

A long day of work did not always end without incident. The two brothers ran out of seeds. Bata had to urgently return home for them. In addition, one of those accidents occurred that the scribe, who so disliked agriculture, spoke about. One of the cows tripped and fell. She almost broke the drawbar and dragged the second cow with her. The plowman runs up to her. He unties the unfortunate animal. He picks it up. And soon the team moves on as if nothing had happened.

Although the Egyptian fields were quite monotonous, they were not as monotonous as they are today: in the old days there were trees on them. Spreading sycamores, tamarisk, jujube, balanites and persea with green spots enlivened the black plowed earth. These trees served as material for agricultural tools. Their shadow graciously covered the plowman, his basket of provisions and a large jug of fresh water. In addition, he hung a wineskin on a sycamore branch and drank from it from time to time.

But then a break came: the team had to rest. The plowmen exchange comments:

"Nice day" is fresh today. The team is pulling. Heaven fulfills our wishes. Shall we work for the master?"

Paheri himself just shows up to see how things are going. He gets off the chariot, and the groom holds the reins and calms the horses. One plowman notices the owner and warns his comrades:

Hurry up, counselor!

Drive the cows!

Look, the prince is standing

And he looks at us.

This Paheri did not have enough cows for all the plows, and he was afraid that the land was about to dry out. Therefore, instead of cows, four men were harnessed. They console themselves for this hard labour song:

“We will do it, we are here. Don’t be afraid of anything in the field! It’s so beautiful!”

The plowman, an obvious Semitic and obviously a former prisoner of war, like his comrades, happy that he escaped their fate, answers them with a joke:

“How beautiful are your words, my little one! Beautiful is the year when it is free from disasters. The grass is hard under the feet of the calves. It is the best!”

Evening comes, the cows are unharnessed and rewarded with food and kind words: "Hu(eloquence) - among bulls. Sia(wisdom) - in cows. Feed them quickly!"

Having gathered the entire herd, they drive it to the village. The plows remain in the care of the plowmen. If you leave plows in a field unattended, it is unknown whether they will be found the next day. As the scribe says:

“He will not find it (the team) in place. He will look for it for three days. He will find it in the dust, but will not find the skin that was on it. The wolves tore it to pieces.”

The Egyptians covered the seeds with soil not only with the help of a plow. Depending on the terrain, they used a hoe and a spade for this. The hoe was no less primitive than the plow. It was shaped like the letter A, one side of which was much longer than the other. The hoe wore out even faster than the plow, and the peasant had to repair it at night. But this didn’t seem to upset him.

“I will do more than the master ordered,” says one worker. “Quiet!” - “Hurry up with your business, my friend!” answers the other. “You will free us in time!”

On lands that had been under water for a long time, from all these hard work got rid of in the following way: herds were released into the sown fields. Bulls and donkeys were too heavy for this, so in ancient times sheep were used. A shepherd with a bait in his hand led the leader ram, and behind him the whole flock rushed to the field. For reasons unknown to us, in the era of the New Kingdom, pigs, which Herodotus himself saw in the fields, were used for the same purposes.

Lowering the grain into the ground led the Egyptians to serious thoughts, or more precisely, to thoughts about burial. The Greeks note that during the sowing season they performed ceremonies, as at funerals or on days of mourning. Some found these customs tedious, others justified them. In the texts that have come down to us from the times of the pharaohs, from which I was able to describe the field work of the peret season, almost nothing is said about these rituals. The shepherds, driving their sheep to the field, sang a plaintive song; it was repeated when the sheep trampled the compressed ears of corn laid out on the threshing floor:

Here is a shepherd in the water of fish.

He talks to the catfish

He greets Mormir.

O West! Where is the shepherd, where is the shepherd of the West?

A. Moret was the first to suspect that this couplet was not just a joke of peasants ridiculing a shepherd trampling in the mud. For fish are not found in the mud, and especially not in the drain where the ears of corn are dried. The Shepherd of the West is none other than the first drowned man, the god Osiris; Seth cut him into pieces and threw him into the Nile, where Lepidopus, Oxyrhynchus and Phago swallowed his genitals. Consequently, on the occasion of sowing and threshing, the Egyptians called upon God, who gave man useful plants and was so connected in their minds with these plants that they sometimes depicted him with ears of corn and trees growing right on him.

Herodotus naively believed that after sowing, the Egyptian farmer sat with folded arms until the harvest. If he really did this, he would not reap a decent harvest because even in the Delta there is not enough rain and the fields have to be irrigated, and even more so in Upper Egypt where the land immediately dried out and the grains would immediately wither, like barley in the garden of Osiris, left unattended. Thus, irrigation was a dire necessity. This is exactly what Moses reminded his people of, describing the benefits that awaited them in the promised land:

“For the land into which you are going to possess it is not like the land of Egypt from which you came, where you sowed your seed and watered it with your feet, like an olive garden.

But the land into which you are moving to take possession of it is a land with mountains and valleys and is filled with water from the rain of heaven.”

From this passage it can be concluded that water was supplied to the fields by means of a device that was driven by the feet: however, neither Egyptian texts nor images give reason to believe that the Egyptians had such a machine. But it is quite possible that the managers of the sluices of Lake Meris (modern Birket Karun) opened them when the fields needed watering. The canals were filled with water. Using shadufs or jugs, which was much more difficult, it was poured into irrigation ditches. They were opened and closed one by one, new ones were dug, dams were erected, and all this was done with feet, as in one Theban painting, where clay for pottery is kneaded with feet.

5. Harvest

As soon as the ears of corn began to turn yellow, the farmer fearfully awaited the invasion of his enemies: the owner or his representatives, guards, a cloud of scribes and land surveyors, who first of all began to measure the fields. Then they determined the amount of grain using Egyptian measures, and one can imagine quite accurately how much the farmer had to give to the royal treasury or to the priests of such a god as Amon, who owned the best lands countries.

The owner or his representative left the house early in the morning. He drove the chariot himself, holding the reins with a firm hand. Servants followed him on foot, carrying chairs, mats, bags and caskets - everything the scribes would need to count the harvest, and much more. The chariots stopped near a group of trees. From nowhere, people appear unharness the horses, tie them by one leg to the trees, and bring them water and food. At the same time, they build a stand for three large jugs. From the caskets they take out bread, various provisions, which they put on plates and baskets, and even toiletries. The groom settles down in the shade and falls asleep, knowing that he can rest peacefully for several hours. The owner is already conferring with land surveyors. He is in formal clothes: he is wearing a wig, a short-sleeved shirt with a belt over a loincloth, a necklace on his chest, and a staff and scepter in his hands. He has sandals on his feet. His assistants are content with loincloths. Only a few are wearing sandals, the rest are barefoot.

My surveyors are also dressed in formal attire - a shirt with short sleeves and a pleated skirt. They distribute among themselves tools, rolls of papyri, writing tablets, bags and bags in which they carry brushes and ink, coils of cord and stakes about three cubits long. When surveying the fields of Amun, the most greedy and rich of all the Egyptian gods, surveyors use a cord wound around a block of wood. Decorated with the head of a ram, because the ram is the sacred animal of Amun.

The head of the surveyors finds a boundary stone. He determines, calling the great god in heaven to witness, that the stone is exactly in place. He places his scepter on it, reminiscent of the symbol of the Theban nome, while his assistants unwind and tighten the cord. Children wave their hands, driving away the quails that flutter over the ripe ears of corn. Of course, this scene brings together not only interested parties. Next to those who are busy with business, there are a crowd of curious people who give them advice. The land surveyors would have long ago exhausted themselves from the hot sun if a devoted maid had not brought them a drink during a hearty afternoon snack in the shade of the sycamore tree.

The harvest and threshing continued for many weeks. There were not enough agricultural workers. In the domains of the state and the great gods, seasonal workers were recruited, who first harvested the crops in the southern nomes, and then moved to the northern ones, where other fields were already waiting for them, ready for the harvest. After the harvest ended in Upper and Middle Egypt, it was just beginning in the Delta. Nomes were supposed to supply nomadic seasonal workers. We know for sure about its existence from the decree of Seti I, by which he exempts his temple - the “House of Millions of Years” in Abydos - from this duty.

The reapers cut the ears with a sickle with a short, convenient stream. The sickle blade had a wide base and a sharp end. The Egyptians did not even try to cut the ears of corn close to the ground. They walked, bending slightly, took a good bunch of ears of grain into the handful of their left hands, cut them from below with a sickle and laid them on the ground, leaving a rather high awn behind them. Behind them were women who collected the cut ears of corn into baskets made of palm branches and carried them to the edge of the field. Several women had bowls for collecting spilled grain. It is unlikely that straw was left to rot in the fields, but we know nothing specifically about this.

Landowners were sometimes depicted in the field, where they themselves reaped and collected ears of corn. In these images they are wearing the same formal white ruffled clothing. The idea arose that they made, so to speak, the beginning, and then gave way to the real reapers. But in reality, the artists depicted an episode from future life in the afterlife fields of Ialu, where there was plenty of everything, but everyone had to work for themselves. This is exactly what Mena did - sitting on a stool with crossed legs in the shade of a sycamore tree next to all kinds of dishes.

Work began at dawn and ended only at dusk. Under the hot sun, the reapers stopped from time to time, took the sickle under their arms and drank a mug of water.

“Give plenty to the farmer and give me water so that I can quench my thirst.” In ancient times, people were more demanding. One of them says: “Beer for the one who reaps barley!” (Perhaps because beer was made mainly from besh barley?) Reapers who stopped too often were immediately sternly reprimanded by the overseer:

“The sun is shining, everyone sees it. But they have not yet received anything from your hands. You have tied at least one sheaf, do not stop anymore and do not drink on this day until you finish the work!”

The reapers languished under the sun, and several people sat in the shade, their heads on their knees. It is unknown who they are - workers who have escaped the watchful eye of the overseer, curious onlookers, or servants of the owner waiting for him to finish his business. Among them we also see a musician sitting on a sack and playing his flute. This is our old friend because we have already seen him in the tomb of Ti (Chi) times Ancient kingdom, where a similar musician with a flute two cubits long followed a row of reapers. In front of him walked one of the reapers, who beat his hands, without releasing the sickle from under his hand, and sang a bull-driver's song, and then another, which began with the words: “I have set out, I am coming!”

Thus, the overseer's anger was most likely for show. Paheri does not have flutists, but the reapers themselves improvise a dialogue song:

What a beautiful day!

Come out of the ground.

The north wind is rising.

Heaven fulfills our wishes.

We love our job.

The gathered onlookers do not wait until the entire field is harvested and pick up missed ears or beg for fallen grain. These are women and children. Here is one woman holding out her hand and asking: “Give me at least a handful! I came [yesterday] evening. Don’t be as angry today as you were yesterday!”

To this, the reaper, who was approached with a similar request, responds quite sharply: “Get away with what you have in your hand! You’ve been kicked out for this more than once.”

In very ancient times it was the custom to give the workers at the end of the harvest as much barley and other grains as they could reap in one day. This custom continued throughout the era of the pharaohs. In Petrosiris, when the reapers worked for the master, they said: “I good worker who brings grain and fills two granaries for his master even in bad years by the diligence of his hands with the grains of the field, when the season of "akhet" comes.

But now it's the turn of the reapers. And they say: “Let those who made the fields abundant on this day rejoice twice! They left for the peasants everything they collected.”

Others, although they complain that little was left for them, still argue that even this little is worth collecting:

“A small sheaf for the whole day, I work for it. If you reap this one sheaf, the rays of the sun will fall on us, illuminating our labors.”

Fearing thieves and voracious birds, the grain was immediately taken away. In the Memphis area, harvested ears of corn were transported on donkeys. Here a whole line of donkeys, led by a driver, arrives at the field, kicking up clouds of dust, The sheaves are thrown into rope pack bags. When they are filled, more sheaves are placed on top and tied with ropes. Donkeys carry a load, donkeys jump in front of them, about which no one cares, and the drivers joke or scold, waving sticks: “I brought four jugs of beer!” - “While you were sitting (idle), I carried 202 bags on my donkeys!”

In Upper Egypt, donkeys were also sometimes used, but usually the harvested ears of grain were carried by people. Perhaps that is why, in order to shorten the harvest time, the ears of corn were cut very short, leaving long straw in the fields. The ears of corn were carried away in rope nets stretched over wooden frames with two handles. When such a net was filled and it was no longer possible to add even a handful of ears of grain to it, a pole four to five cubits long was inserted into the rivers of these stretchers and secured with knots. Two porters lifted a pole onto their shoulders and carried a net of ears of corn to the threshing floor, chanting cheerfully, as if to prove to the scribe that their fate was no worse: “The sun is shining in the back. And we will give Shu a fish for barley!”

One of the scribes urges them on, saying that if they don't hurry, they will be caught by another flood. He says: “Hey, hurry up! Move your legs! The water is already coming. Now it will reach the sheaves!”

He's exaggerating, of course, because the next Nile flood is at least two months away.

This scene is replaced by another. One porter took hold of the stretcher pole with the ears of grain. The other one also takes the pole, but is clearly trying to slow down the rhythm of work. He says: “My shoulder doesn’t like this net with ears of grain. How heavy it is, oh my heart!”

The ears are scattered on the drain, where the ground is well trampled. When the layer of ears is thick enough, bullock drivers with whips and workers with pitchforks enter the current. Bulls trample on the threshing floor, and workers shake the ears of corn with pitchforks. The heat and dust made this work difficult. And yet the driver urges the oxen:

"Thresh for yourself, thresh for yourself,

O bulls, thresh yourselves!

Grind straw for your feed.

And the grain is for your masters.

Do not stop,

It's cool today.Translation by M.E. Mathieu

From time to time some bull bends down and picks up everything he can find - straw and grain, but no one pays attention to it.

When the oxen were taken away, the workers were still trying to partially separate the grain from the straw with pitchforks. The chaff, softer than the grain, ended up on top. It could be swept away with brooms. In the end, a kind of colander was used for this. The worker filled it with grain, took it by the handle, stood on tiptoes as high as possible and poured out the grain so that the wind would blow away the chaff.

But now the grain is cleaned. The scribes get down to business with their supplies and grain measures. Woe to the farmer who tried to hide part of the harvest or, even with the best intentions, failed to reap the harvest that was expected from his field. The culprit is put on the ground and beaten, and in the future, perhaps, more severe punishments await him. Workers carrying baskets full of grain pass between the scribes and enter a courtyard surrounded by high walls where sky-high granary towers stand. These sugarloaf-shaped towers are carefully plastered on the inside and whitewashed on the outside. The porters climb the stairs to the hole, where they pour the grain. Later, when needed, it can be raked out through the small door at the bottom of the tower.

In general, all these hard work are having fun. One or two blows with a stick are quickly forgotten. The farmer is used to this. He took comfort in the fact that the stick in his country was the lot of many and walked on the backs of the less accustomed. The words of the author of the psalm were quite suitable for the Egyptians:

Those who sow with their servants will reap with joy.

Weeping, the one who bears the seeds will return with joy.

Carrying your sheaves.

When the grain was lowered into the ground, they mourned the “Shepherd of the West.” Now the harvest is harvested, everyone is happy, but we must thank the gods. It was believed that while the grain was winnowed, it was protected by an idol in the form of a crescent moon swollen in the middle. What meaning was put into this image! Answering this question, we can note that to this day the peasants of Fayum install on the roof or hang above the door of the house a scarecrow in a skirt made of ears, which they call “arus” - “bride”. They present this “bride” with a cup of drink, eggs, and bread. Many thought, and apparently not without reason, that the ancient Egyptian idol in the form of a crescent moon was also called the “bride.”

At the same time, farmers brought abundant sacrifices to the snake goddess Renenutet, who, as we know, was honored by winegrowers, in the form of sheaves of wheat, cucumbers and watermelons, bread and various fruits. In Siut, each farmer offered the first fruits of his harvest to the local god Upuatu. Pharaoh himself donated a sheaf of wheat to the god Min in front of a large crowd of people on the day of his festival in the first month of the Shemu season. From great to small, everyone thanked the gods who give everything that exists, and looked forward with hope to a new flood of the Nile, which was supposed to resume the cycle of life.

6. Flax

Len grew tall and tough. Usually it was pulled out at the time of flowering. In color images in the tomb of Ipui and Petosiris, the stems are topped with small blue spots. .Cornflowers grow between them.

To pull flax out of the ground, it was grabbed quite high with both hands, trying not to damage the stem. Then they shook off the soil from the rhizomes and laid the stems in a row, leveling them from the roots. Then they collected the stems into sheaves so that the flowers stuck out on both sides, and tied them in the middle with a rope of the same stems that had to be sacrificed. The Egyptians knew that the best and most durable fiber came from flax that had not yet reached full maturity. In addition, one of the ancient texts strongly advises plucking flax at the time of flowering. However, it was necessary to save part of the crop until full maturity in order to obtain seeds for the next sowing, as well as for medicine.

Workers carried sheaves of flax on their shoulders, children - on their heads. The lucky ones who had donkeys filled saddle baskets with flax and ordered the drivers to ensure that not a single sheaf fell out along the way. A man is already waiting for them at the spot, beating a sheaf of flax on an inclined board. He shouts to them: “Hurry up, old man, and don’t talk too much, for the people from the fields are coming quickly!”

The old man replies: “When you bring them to me 1109, I will comb them!”

The maid Rejedet, who was probably confused by the devil, chose precisely such a moment to inform her brother about her mistress’s secret. She got a lot of trouble for this, because her brother had just a sheaf of flax in his hands - the most suitable thing with which to whip an immodest girl.

7. Field pests

We already know that the harvest was threatened by numerous enemies. When the ears of corn were full and the flax was blooming, thunderstorms and hail fell on the fields of Egypt, and with them people and animals devastated them. The seventh plague of Egypt was the locust, carried by the east wind, which destroyed everything that remained: not a leaf on the trees, not a blade of grass on the fields. In the face of such enemies, the peasant could only ask for the intercession of the gods, and above all appeal to the god of the locust. But with some unwanted guests who visited his gardens in spring and autumn (orioles - "genu" and rollers - "surut"), he himself could fight quite successfully. These useful birds, which destroy many insects, become enemies of the peasant when the fruits ripen. Artists depict them circling over fruit trees. Hunters catch them in large nets stretched over trees using stakes. The net does not prevent the birds from getting to the fruit, but when there are a lot of birds gathered, the children quietly approach the tree and pull out the stakes. The net falls, covering the tree and the feathered thieves. The hunters enter this light cage, collect the birds as fruits and put them in cages. In addition to nets, the Egyptians used spring traps, known since ancient times.

During the migration period, quails fly to Egypt in clouds. They are so tired after a long flight that they fall to the ground. Of course, the Egyptians preferred to catch healthy birds. The relief, kept in the Berlin Museum, shows us six hunters with a fine-mesh net stretched over a wooden frame. The hunters' costume is noteworthy. They wear sandals to walk on the stubble, and are belted with white scarves. When flocks of quail appear above compressed field, the hunters jump up and begin waving their white scarves, causing panic among the birds: the confused quails begin to rush about and eventually fall into the net, get their paws entangled in small meshes, interfere with each other and cannot free themselves in time. Four hunters carefully lift the frame with the net, and two select the caught quails from it.

The families of farmers willingly feasted on quails, and the gods did not neglect them. For example, Amun received 21,700 quails as a gift during the reign of Ramesses III. This figure is approximately one sixth of total number birds donated to Amon at the same time.

8. Livestock

For a long time, the ancient Egyptians "selected animals by touch that could be usefully tamed and domesticated. A man became friends with a dog while hunting. The ox and the donkey turned out to be useful for transporting goods. The nomads greatly valued sheep's wool, while the Egyptians considered it unacceptable neither for their dead nor for the living. They preferred goats to sheep. In addition to these animals, which they managed to quickly domesticate, just like the pig, the Egyptians hunted and kept gazelles, deer, saber-horned antelope, oryx, and cow antelope in their pens ( bubals), stone goats, Mendes antelopes, addaxes and even disgusting hyenas. During the Middle Kingdom, the ruler of the nome Oryx kept in his pens several animals, after which this nome was named. During the New Kingdom, the Egyptians abandoned such experiments. One of the schoolchildren received this reprimand:

“You are worse than a goat in the mountains who lives by running, he has not spent [a single] half day plowing, and has not stepped [yet] on a current at all” (Translation by M.A. Korostovtsev).

Thus, the Egyptians limited themselves to only the most useful animals for humans; they were a horse, an ox, a donkey, a goat, a ram, a pig, a goose and a duck. The camel was known only to the inhabitants of the Eastern Delta. As for chickens, they appeared much later. Of course, other animals also received attention and caring care, but mainly in temples, where they were revered as gods.

The horse was known in Egypt shortly before the time of the Ramessides and, despite the indemnities imposed on Asian peoples, is still quite rare in Egypt. The Khevi had a stable, which was separate from the ox stable and the donkey pen. But Khevi was the royal son of Kush and occupied one of the first places in the state, he is one of the privileged few who rode out in his chariot, heading to the palace, for a walk or to inspect his possessions. Horse owners did not dare to ride them. Only two or three times, as far as we know, Egyptian artists depicted horsemen. The nomads were much braver. During military operations, when the chariot was damaged, they unharnessed the horses, jumped on them and rushed away. In the meadows, horses were grazed separately from other animals.

The stable for the bulls was usually located not far from the owner's house, next to the grain barn, in the same fence. Servants also spent the night there to guard the bulls and lead them out in the morning. In small adobe huts, black inside and out, they managed to prepare dinner from their meager supplies that were immediately stored. Servants, heavily laden, walked in front of or behind the herd. To lighten the load, they distributed it into two equal parts - in jugs, baskets or bundles, which were carried on rockers. If they only had one place - a bundle, a jug, etc. - they carried it on a stick slung over their shoulder. Bata did this, but he was very strong guy! Women looked at him. And most of the shepherds are unfortunate poor people, overworked: bald, sick, with a sparse beard, with a big belly, and sometimes so skinny that it’s scary to look at! In one of Meir’s tombs, a merciless artist depicted them exactly like this without any embellishment.

The life of shepherds could not be called monotonous. If a shepherd loved his animals, he constantly talked to them and, knowing the places with the best grass, took his favorites there. The animals responded to him with devotion and by growing quickly, gaining fat, and bearing large offspring. And on occasion, they themselves provided some service to the shepherd (“The Tale of Two Brothers”).

It was always difficult for a shepherd to cross the swamps. Where people and adult animals did not lose ground under their feet, the calf could drown. Therefore, the shepherd threw him on his back and resolutely walked into the water. The mother cow followed him with a pitiful moo, her eyes wide in fear. The wise bulls, accompanied by other shepherds, walked calmly, maintaining order. If the place was deep, and nearby there were thickets of reeds and papyrus, one should be wary of crocodiles. But the shepherds of ancient times knew what word to say so that the crocodile would immediately turn into a harmless plant or to blind it. I guess these magic words were not forgotten in the era of the Ramesses, but documents on this matter are silent. In the tomb at El Bersha there is preserved the song of a shepherd who passed through many countries:

You have trampled the sands of all deserts,

And now you are trampling the grass.

You eat thick grasses,

Now you're finally full

It's good for your body!

In Petosiris, the shepherd gives his cows poetic names: Golden, Sparkling, Beautiful, as if they personified the goddess Hathor, to whom all these epithets belong.

Matings, the birth of calves, bullfights and constant marches were the main moments when the shepherd could show his knowledge and dedication. If he gets into trouble, so much the worse for him. If a crocodile grabbed a calf, if a thief stole a bull, if disease ravaged the herd, no explanation was accepted. The perpetrators were laid on the ground and beaten with sticks.

An excellent remedy against cattle theft was branding. It was resorted to mainly in the domains of Amon and other great gods and in the royal domains. Cows and calves were herded to the edge of the meadow and taken one by one with a lasso. They tied their legs and threw them on the ground, as if they were going to kill them, then they heated an iron brand on the grill and applied it to the animal’s right shoulder blade. The scribes, of course, were present at this operation with all their accessories, and the shepherds respectfully kissed the ground before these representatives of the authorities.

Here the goats scatter throughout the grove, the trees of which are intended for cutting down, and in the blink of an eye they eat up all the greenery. They are in a hurry for good reason, because the woodcutter is already here, ready. He's already struck the first blow with an axe, but that won't stop the goats! Little goats are jumping around. Goats don't waste time either. But now a shepherd with a staff gathers his flock. At one end of the beam he carries a large bag, and at the other, in the form of a counterweight, a kid. In addition, he has a flute in his hand, but not a single Theocritus and not a single Virgil has yet sung the love of shepherds and shepherdesses on the banks of the Nile.

The Egyptians raised birds in special pens that did not change from the Ancient to the New Kingdom. In the middle poultry yard, as a rule, there was a stele or statue of the goddess Renenutet. In one corner of the yard there was a canopy, under which there were jugs, bags and scales for weighing grain; in the other corner, separated by a net, there was a large puddle. Geese and ducks swim in it or wander along the shore when the poultry farm brings them another portion of grain.

9. Swamp inhabitants

Swamps covered a large part of the Nile Valley. When the river returned to its banks, here and there large puddles remained in the cultivated fields, in which the water did not dry out until the end of the shemu season. These swamps were covered with carpets of water lilies and other plants, and along the banks there were thickets of reeds and papyrus. Papyrus sometimes grew so thick that the sun's rays did not penetrate through it, and was so tall that the birds nesting in its umbrellas felt safe. These birds showed miracles of aerial acrobatics. Here the female is hatching eggs. Nearby, an owl awaits nightfall. However, the natural enemies of the feathered tribe, a civet or a wild cat, easily get to the bird's nest. The father and mother desperately fight the robber, while their chicks call for help and flap their still bare wings to no avail.

Flexible fish slide between the reed stalks. Particularly noticeable among them are mullets, catfishes, mormirs (“Nile pikes”), huge lates, almost equally large chromis and fahaki, which, according to G. Maspero, nature created in a moment of good-natured fun. But the batensod swims belly up. She loved this pose so much that her back turned white and her belly darkened. A female hippopotamus found a secluded place to give birth to her baby. A cunning crocodile is waiting for an opportunity to swallow a newborn, unless his menacing father returns. Then a merciless struggle will break out, from which the crocodile will not emerge victorious. The hippopotamus will grab him with its huge jaws. In vain the crocodile grabbed his leg: he lost his balance and the hippopotamus bites him in half.

The further north you go, the more extensive the swamps become, the denser the thickets of papyrus. The Egyptian name for the Delta - "mekhet" - also means a swamp surrounded by papyrus. The Egyptian language, so rich in synonyms for natural phenomena, had special words for different swamps: a swamp overgrown with water lilies is “sha”, a swamp with reed thickets is “sekhet”, a swamp with waterfowl is “iun”, and puddles of water left after a spill are “pehuu”. All these swamps were a true paradise for hunters and fishermen. Almost all Egyptians and even future scribes the slightest possibility went to the swamps to hunt or fish. Noble ladies and the little girls applauded the successful hunters and were happy to return home with the live bird they had caught. And the boys quickly mastered throwing a boomerang or harpoon. But all this was amateur fun. In the north, people lived off the swamps.

Fishing image

The swamps provided them with everything they needed for housing and for making tools. The Egyptians cut papyrus, knitted large sheaves from the stems and, bending under the weight of their burdens, and sometimes stumbling, walked with them to the village. Here they laid out their spoils on the ground and selected stems suitable for building a hut. For instead of houses made of raw brick, papyrus huts covered with silt were built here. The walls were thin, the plaster often fell off, but is it really difficult to cover up the cracks? Ropes of any thickness, mats, nets, chairs and cages were woven from papyrus fibers and sold to residents of arid regions. Elegant, practical shuttles were tied with ropes from papyrus stems, without which it was impossible to hunt or fish. But before we set off for the loot, we had to test the new boat. Wearing a wreath of wildflowers and a water lily around his neck, each one brought his shuttle onto the surface of the water with the help of a long pole forked at the end. The battle began with an exchange of curses, sometimes quite violent. Terrible threats were made and blows rained down. It seemed that all this would not end well, but the opponents only tried to push each other into the water and overturn the shuttle. When only one winner remained on the water, the holiday ended. The winners and losers, having reconciled, returned to the village together and continued to practice their craft, which one mocking Egyptian called the hardest.

Fishermen went for long-distance fishing on single-masted wooden boats. Ropes were stretched between the shrouds to dry the fish. Sometimes birds of prey sat on the mast.

There were many ways to catch fish. A lone fisherman would settle down with his supplies in a small canoe, find a quiet place and throw a fishing line into the water. When a large fish was hooked, he carefully pulled it to the shuttle and stunned it with a club. In shallow swamps, simple tops or tops from two sections were placed. Attracted by the bait, the mullet found an entrance to the top, pushed the stems apart, but could not get back out. Soon the top turned into a fish tank with live fish. The successful fisherman feared only his neighbor, who could track him down and be the first to arrive at the top.

Fishing with a net required patience and a steady hand. The fisherman stopped the shuttle at a fishing spot, loaded the tackle and waited. When the fish itself entered the net, it had to be lifted quickly, without making any sudden movements, however, otherwise the fisherman would only lift the empty net.

Drag fishing required a dozen men, at least two boats, and a huge rectangular net with floats on the top edge and stone weights on the bottom. The drag was stretched out in the lake and fish were driven into it. Then he was slowly pulled towards the shore. The most crucial moment was coming, because such dexterous and strong fish as the one-tooth from the catfish family easily jumped over the bridge and broke free. Fishermen had to catch the fugitives on the fly. And for the extraction of huge lates, so large that the tail dragged along the ground when two fishermen carried this fish suspended from a pole, the most best weapon there was a harpoon. Harpoons were also used to hunt hippopotamuses, but an ordinary harpoon would have broken like a reed in the body of this monster. To hunt hippopotamuses, powerful harpoons with a metal tip attached to a wooden shaft and a long rope with many floats were used. When the harpoon pierced, the shaft broke, the tip remained in the body of the hippopotamus, which tried to escape from the hunters. And they watched the floats, picked up the rope and pulled it up. The hippopotamus turned its huge head towards the hunters and opened its mouth, ready to break the shuttle. However, he was finished off with harpoons.

Hunting with a boomerang was more of a sport for the rich than a real industry. We see Ipui taking a seat on a luxurious boat shaped like a giant duck. However, most hunters were content with ordinary sickle-shaped papyrus boats. It is very important that there is a goose in the boat that is trained to attract geese. The hunter throws a boomerang with a snake's head on one end. The boomerang and the downed game fall. The hunter's friends, his wife and children quickly pick up the prey. The delighted little boy tells his father: “I caught an oriole!” But during this time the wild cat manages to grab three birds.

Hunting with a net made it possible to catch many birds at once. It was a sport, I participated here the whole team. "Princes" and people high position did not hesitate to take part in this hunt as leaders and even simple signalers. On flat terrain, a rectangular or oval reservoir several meters long was chosen. On both sides of this puddle were stretched two rectangular nets, which, if connected, would cover the entire surface. It was only necessary to suddenly and simultaneously throw both nets so that all the birds that landed on the water would be captured at once. To do this, two poles were driven into the ground on each side of the reservoir, on the right and left. Two trap nets were tied to them, two external corners which were connected by ropes to a thick stake driven at a distance on the axis of the reservoir, and the other two - to the main rope more than ten meters long, with the help of which this trap was slammed. When everything was prepared, the signalman hid nearby in the thickets, often knee-deep in water, or sat behind a wicker shield with holes. Trained birds, accomplices of the hunters, hobbled along the shore of the reservoir. Soon flocks of wild ducks descended on him, and three or four hunters were already holding on to the release rope. They were quite far from the reservoir, because at the slightest noise the birds would fly away. The signalman raises his hand or waves his handkerchief. At his sign, the hunters sharply lean back, pull the rope, and the trap is triggered. Two nets fall simultaneously on a flock of birds; in vain they struggle desperately, trying to get out of the net. Without allowing them to come to their senses, the hunters, who had fallen to the ground from the sudden jerk, quickly get up and run up with the cages. Having filled them, they tie the wings of the other birds, crossing the flight feathers: this is enough to carry them to the village. All these methods required patience, dexterity, and sometimes courage, but all their efforts would have remained in vain if not for the patronage of the goddess, whom they called “Sekhet” - “Field”. She was depicted as a peasant woman in a simple straight dress. Long hair fell onto her shoulders. And the network itself was a deity named “Network” and was considered the son of “Field”. Hunting and fishing, which we have described, were under the protection of the goddess Sekhet. Fish and birds were her subjects, but she did not skimp and distributed them to her friends - hunters and fishermen.

10. Hunting in the desert

Hunting in the desert was a sport for “princes” and other nobility, as well as an activity for professional hunters. On the one hand, there is practically not a single tomb where there would not be an image of its owner, striking with well-aimed arrows gazelles and antelopes gathered in a close herd, as in some fenced reserve. But, on the other hand, we see how archers patrolling in the desert and the overseers of the golden mountain of Koptos come with a report to the great priest of Amon Menkheperraseneb, accompanied by the head of the hunt, who presents the god with magnificent prey: ostrich eggs and feathers, live ostriches and gazelles and carcasses killed animals. Ramses III created detachments of archers and professional hunters who were supposed to accompany the collectors of honey and fragrant resins and at the same time catch oryxes in order to present them to the Ka of the god Ra at all his festivals, for the offering of desert animals from ancient times, when man lived mainly by hunting, and before historical era was considered especially pleasing to the gods.

Amateurs, and even professionals, tried to avoid long pursuit of game, which nature had endowed with fast legs, because they risked getting lost in the desert, where they themselves would become prey for hyenas and birds of prey. Knowing well the habits of animals and places of watering places, they tried to drive as much game as possible into a pre-prepared area, where they could easily catch or kill it. To do this, they chose a deep valley, where there were still remnants of moisture and some greenery, but always with such steep slopes that animals could not climb them. The valley was blocked across with nets on stakes in two places; The distance between the two barriers was determined by the hunters, but what it was, the images do not show us. They laid out food and water inside. Soon the pen filled up. The animals enjoyed life, not realizing that their hours were numbered. Wild buffalo galloped. The ostriches danced in greeting rising Sun. The gazelle was feeding her calf. The wild donkey fell asleep with his neck stretched out. The hare, sitting on a hill, sniffed the wind.

Previously, hunters went hunting on foot. The gentleman walked lightly. The accompanying people distributed among themselves supplies, bows, arrows, cages, ropes and baskets for game. The hounds led greyhounds and well-fed hyenas, which they managed to train for hunting.

Since chariots appeared in Egypt (i.e., from the New Kingdom), the lord rode out in a chariot, as if going to war, with a bow and arrows. Those accompanying him - "shemsu" - followed him on foot, carrying jugs, full wineskins, baskets made of palm branches, bags and ropes on yokes. When the small detachment arrived at the place, the gentleman with his weapon dismounted from the chariot. The huntsman was holding a pack of greyhounds on leashes. By that time, the Egyptians had long abandoned the hyenas they used during the Old Kingdom.

But suddenly a rain of arrows falls on the game in the pen and angry greyhounds rush. Unhappy animals look in vain for a way out. Steep slopes and nets keep them at the scene of the massacre. Deer and wild bulls have already been defeated. An ostrich fights off an attacking dog with its beak. A pregnant gazelle gives birth to a calf while running, and the greyhound immediately strangles the newborn. Oryx rushes forward with a desperate leap, but falls straight into the mouth of another dog. Another greyhound knocked down a gazelle and grabbed its throat.

Judging by the image in the tomb of a certain Usir, traps were also placed in the enclosure, but the painting was too poorly preserved to be able to judge their design. However, there were certainly traps. Otherwise, how could hunters, armed only with bows and arrows, capture such a large number of live game, as we see in the tomb of the same Usir and in the tomb of Amenemhet?

On the way back, the hunters lead a stone goat, a gazelle, an oryx and an ostrich, tied by the leg. The assistant carries a small antelope on his shoulders. Others are dragging apparently dead hares by the ears. A hyena, suspended from a pole by four legs, hangs head down: it is certainly dead. These hunters wasted no time, but there were those who, not caring about profit or simply out of love for danger, continued to pursue the antelopes on their lightning-fast chariots. This is what the tireless prince Amenhotep did. A certain Userkhet also rode a chariot into the desert, drove horses himself and shot with a bow. He drove a herd of antelopes in front of the chariot, which in their panicked flight carried away hares, a hyena and a wolf. Userkhet returned with rich booty.